Special Report – Catch Shares: Too often we call the devil by a different name – by Evan Connoly ACFN Contributor

Catch Shares represented more than a fishing problem to him. It concerned the control of the American way of life, and the privatization of more and more of the public’s goods.

It was a strange sight to see, and one I had not since my childhood. Plymouth Rock loomed majestically over the ocean in the morning sun beside the town’s historic waterfront. Cold and raw; b oth the day and the feeling in my gut the more I learned about the changes in this town. The streets felt as though they were dying. American sweat and blood now trickled only thinly across those historic streets.

oth the day and the feeling in my gut the more I learned about the changes in this town. The streets felt as though they were dying. American sweat and blood now trickled only thinly across those historic streets.

In Plymouth I met with a group of men who remain fishing in the area. I say “remain” quite intentionally, but back to that later. I received a call from Joel Hovanesian in response to my January piece on quota systems, Catch Shares specifically. What he began to tell me on the phone was counter-point to most higher education had taught me. With my eyes on “societal gains,” I had failed to see the impact that these systems had on small communities. I had failed to see that to favor “efficiency” the Plymouth fleet was reduced from roughly 30 boats before 2007, to just 2 active now. In our rush to conserve the stocks we had failed to conserve the historic communities that built New England.

That was one phone conversation. Joel, a fisherman out of Pt. Judith, drove me with him to Plymouth that day to meet these men. On the journey I found that Joel was like many fishermen: headstrong but certainly not ignorant, a true American in his beliefs. Catch Shares represented more than a fishing problem to him. It concerned the control of the American way of life, and the privatization of more and more of the public’s goods.

Jim Keding, Ron Borjeson, Jeff Good, Steven Welch. I came to find that day that their numbers stretched little beyond those I shared a table with. Before we’d even ordered chowders, a cook approached, humbly seeking local catch direct for the coming season. The customers were tired of imports. There in Plymouth they know what fresh seafood should be.

The Catch Share system did come with a catch: reduction of the sharing. Jim spoke to the misreporting that occurred in the first year of fishing under that system. Boats would fish the George’s Bank and Gulf of Maine line, and report catches where it was most beneficial to them. What at first seemed sinister made sense as he continued. “We [the fishermen] made a gentleman’s agreement not to cross those lines without an observer present. Not many honored that agreement.” The plight? Initial allocation of shares. The shares were allocated based on catch history, which varies greatly year to year for smaller boats. ‘Rolling closures’ in years before Catch Shares forced small boats to push further out, reducing their yearly catch and profitability. And these reductions snowballed until catch shares were brought into play. Yellowtail flounder, fervently guarded by the New England Fishery Management Council today, were in such great abundance shortly before Catch Shares, that the price dropped to $0.18/lb. Fishermen stopped bringing the flounder in as it wasn’t economically reasonable, and lost their quotas to bigger boats because of it. Small boats losing these quotas allows large boats to buy more of those species in a round about sort of way; the sort of destructive fishing practice that Catch Shares were meant to also help reduce. What was marketed to the public as best for the fish stocks may actually be more environmentally degrading and wasteful in terms of discards and bycatch.

I saw the issue evolving before my eyes. It was a strain on these men, who’d worked so very hard. Not that this was my first conversation with a fisherman, by no means, but it was the first where I realized how little control they had of their own industry.

There were many problems going on in the ocean, few attributable to “overfishing”. The cod aren’t “gone” as I indicated in the January article. You’ll simply find them in numbers in the North Seas now, rather than George’s Bank. Small boat fishermen can barely keep up with the astounding number of seals in the Gulf of Maine and Cape Cod Bay. Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act numbers of grey seals in Cape Cod Bay have swelled since 1972. Eating an average of 4-6% of their weight per day (that’s somewhere around 5,000 lbs of fish per year per seal). Conservationists will say that no fish is “removed” from the system by natural predators, but considering that we are actively protect them their numbers are substantially higher locally than they might be “naturally”.

It was Mr. Borjeson that spoke on the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant in the bay regarding yellowtail too. Though monitored, it was discovered that the free floating eggs were actually getting sucked through the cooling system. It wasn’t that this was killing the egg right out, but it would strip an oily covering from the egg that allowed it to remain in the water column. The eggs sank, became fouled or smothered, and died. Yet the power plant pays for none of the lost yellowtail allocation, that pressure falls directly onto the fishermen who are unable to meet the unrealistic expectations set by fisheries management practices. There are yellowtail flounder accountability measures in many fisheries in New England now. Are other fishermen accountable for the yellowtail? Or are there perhaps other forces at work here that we might target our efforts upon?

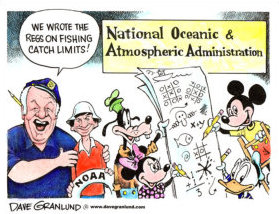

And then there was the issue of NOAA’s surveys which all members at the table scoffed at. NOAA had standardized their trawl surveys, requiring that all be done with specific mesh shape and sizes, rock-hopping gears which miss many groundfish, and the ground cable off. If trawl surveys are not done in the same manner that the fish are caught, how can quotas be set based upon these surveys? And since NOAA refuses to consider most if not all outside data sources, how can members of the industry be assured that the surveys are for their good and not to reduce their quota? The linkage to Catch Shares here is quite obvious: the quota has shrunk, large entities that already control many shares can stay in with the money they have, and small boats that’s can’t afford leases have to sell out of the business. I’d realized by the end of the conversation that I was in fact talking to some of the last fishermen in Plymouth that were their own men. The rest were slowly becoming slaves to corporate-style lease holders. Accumulation caps may not even be enough to solve this issue.

As we drove out of Plymouth I saw the town through a different lens. That lens remained fixed in my eye as Joel and I drove further north to Gloucester. There we met with Bill Scobacz. Thankfully the others had prepared me for the worst, but not like this. Our conversation moved quickly from his young life fishing in New York and Kennebunk to the fleet. Of over 40 draggers, 40 gillnetters, and “somewhere between 7 and 12 transit boats” a much smaller number remain. This is due to the consolidation of the fleets, which is what truly hurts the local economies. Less boats on the water (paired with lower catch limits) means less work for repairmen, gear makers, tug & tow operations, processors, and so forth. Though Catch Shares is, in theory, the most “efficient” practice, it has a butterfly effect felt deeper into these communities than I had ever realized before. This is not to say I was ignorant of the nature of this situation, quite the contrary, though the degree to which it occurred truly astounded me.

“A few guys supported it ‘cause they thought they were going to get rich at the expense of others. They were wrong.” Scobacz asserted about Catch Shares. He and fishermen like him were asked and encouraged to fish for less commercial species during the same year range that was then used to set allocations based on catch history. It seemed as though he believed it was seedy business, though I was unable to elicit much further from him on the matter there.

He spoke also of some aspects of Council business. Scobacz acquired a Days-At-Sea lease from the Seafood Coalition in years recently before the Catch Share program. After submitting his paperwork, and fishing for some time, he was accosted by the Environmental Police. They stated that he had not filled the proper paperwork and docked his boat for three and a half months, a loss of at least 20 very valuable Days-At-Sea in Scobacz’s position. The issue was later “resolved” when an administrator admitted to messing up his leasing paperwork. He was not compensated for lost days monetarily. He was simply given 20 Days-At-Sea back and had his charges dropped. Charges which he never should have had in the first place.

I asked about the theory of Catch Shares; allowing fishermen to fish and sell when they want to get the best prices. Scobacz scoffed a muffled laugh. “Sure we can, but we’re forced to buy our leases from armchair fishermen.” The statement struck me. I suddenly realized the gravity of the Catch Share situation. It had become an issue in which fishermen were forced to either sell out of the business, or buy from monopolistic lease holders with little to no intention of actually catching the fish themselves. They saw the leases as an investment, like a stock. Mr. Scobacz correctly saw the leases as his livelihood.

It’s the inadequacy with which administration deals with some of these fishery issues, and the insensitivity to local economies that drives the frustration of this shrinking working class. More ‘efficient’ measures have been driving small boats out of business since the institution of Catch Shares. Mr. Scobacz left me with one final piece of information which I was previously unaware of. Magnuson was supposed to protect fishermen from an ITQ (individual transferrable quota) system for New England groundfish and associated fisheries. Magnuson demanded that it go to referendum if ever it should become a possibility. However, it was rebranded, slightly altered, and made into something ‘new’: Catch Shares.

Too often we call the devil by a different name.•

Reprinted with permission, Atlantic Coast Fishery News