Choking on good(?) intentions

Nils Stolpe – FishNet USA/Choking on good(?) intentions

Visit FishNet USA click here

In multispecies fisheries, regulators must distinguish between stocks that are truly threatened or endangered and those that are simply fished harder than would be optimal on a single-species basis. It may be best to not try to rebuild some overfished stocks (so long as they do not continue to decline) if the cost in lost catch of other species is too high. (Ray Hilborn, Why Fishermen Oppose Stock Rebuilding Plans, National Fisherman, May 2000)

I recently came upon a report, Addressing Uncertainty in Fisheries Science and Management (it is available at http://tinyurl.com/hcuryq6, the appendices at http://tinyurl.com/zst7jxz), funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through the National Aquarium in Baltimore. The Report’s preface states that it is “primarily directed toward fisheries scientists, managers, policy makers and other participants in the U.S. fisheries management process,” and the panel of experts brought together for the exercise focused on four general sources of uncertainty, which were:

- Data Uncertainty: Fisheries dependent and –independent data that are collected and incorporated into assessments or other scientific management advice have sampling variability. Data uncertainty may also include cases referred to as “data-poor” or “data-limited” where there are insufficient data to support comprehensive scientific assessments.

- Model and Assessment Uncertainty: These are uncertainties that arise during the modeling and assessment process. They include process and parameter uncertainty, accuracy of assumptions, choice of modeling approach and forecasting-related uncertainties. These and other factors can result in retrospective inconsistencies. This type of uncertainty becomes an acute challenge in data-poor or data-limited situations.

- Ecosystem or Population Uncertainty: Ecosystem changes such as long-term oscillations or directional shifts are often beyond the scope of factors currently considered in single-species stock assessments. While they arise explicitly in data, models and assessments, this special set of challenges includes unknown or poorly understood ecosystem relationships and their effects on single-species management advice.

- Outcome and Implementation Uncertainty: There are two components of this source of uncertainty. Outcome uncertainty reflects whether the fisheries management system is setting the right target and limit and is affected by the cumulative impact of data, model and ecosystem uncertainty. Implementation uncertainty addresses whether or not the established target is being accurately met. Uncertain performance of management strategies in response to changing behavior of fishermen and other stakeholders operating within the management system can also introduce new uncertainty.

As far as they go, nobody should have any problems with these general sources of uncertainty, with the report or with the panel that created it. But they don’t go anywhere near where they should be going.

Needless to say, each of them is, when combined with the precautionary principle, designed to result in less fish to the fishermen. They are emblematic of the myopic view of our domestic fisheries that has been effectively sold to the public and the pols that “healthy” fish stocks automatically mean healthy fisheries. While the report is purportedly directed towards “fisheries scientists, managers, policy makers and other participants in the U.S. fisheries management process,” for a large number of those other participants, U.S. fishermen and those whose businesses depend on fishermen and fishing, it’s about as far off target as it’s possible to be. As we’re seeing while our fish and shellfish stocks continue to thrive, there’s a lot more to having healthy fisheries than having healthy stocks.

But this is something that has been forgotten since the Magnuson Act became law in 1976. The Act starts off “the fish off the coasts of the United States, the highly migratory species of the high seas, the species which dwell on or in the Continental Shelf appertaining to the United States, and the anadromous species which spawn in United States rivers or estuaries, constitute valuable and renewable natural resources. These fishery resources contribute to the food supply, economy, and health of the Nation and provide recreational opportunities.” In the intervening forty years the focus has shifted from healthy fisheries – in terms of contributing to the food supply, economy and health of the Nation – to healthy fish stocks, with little or no regard given to why those healthy stocks are or should be desirable. Having healthy fish stocks, which started out as a means to the end of having healthy fisheries, has been distorted into an end in and of itself.

That’s why over ninety percent of the seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported.

We have fisheries that are on the verge of collapse while the fish stocks that support them are healthy. There is a wanton disregard for the health of the businesses that depend of fishing, a disregard that wasn’t really there until the environmental community, funded by a handful of “charitable” mega-foundations (including the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation), started to interfere in the federal fishery management process. Having healthy fish stocks, their supposed goal, is meaningless without healthy businesses benefitting from the utilization of those stocks.

Today the economic effects of management actions on fishing and fishing dependent businesses are at best given lip service; the only thing that really matters when management decisions are considered is whether or not “overfishing” will be ended.

The argument for the almost total focus on the health of the stocks, a concept that is exemplified by the above four sources of uncertainty from a study that was paid for – surprise, surprise! – by one of the mega-foundation that has spent many millions of dollars on “fixing” fisheries, is that healthy fish stocks are supposed to mean healthy fisheries. The present condition of the New England groundfish fishery shows how wrong that supposition is.

In “A synoptic view of the stock status of the twenty Northeast groundfish stocks in 2015” NOAA/NMFS reports that overfishing is occurring in six of the twenty stocks (and that the overfishing status is unknown in one). Overfishing is not taking place in 65% of the New England groundfish stocks (http://tinyurl.com/j7unuqg). The assumption is that two-thirds of these stocks are supporting healthy fisheries.

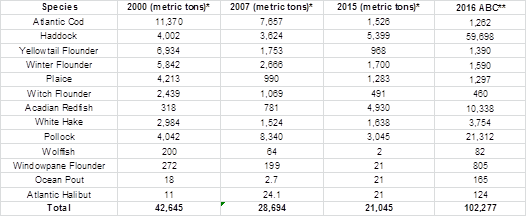

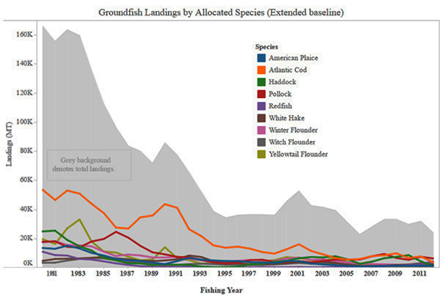

The thirteen fish species listed below are covered by the Northeast Multispecies Fisheries Management Plan – the New England groundfish fishery. Over the last decade and a half the total annual landings of groundfish have declined by fifty percent, at this point being approximately one fifth of what they could be if the acceptable biological catch (ABC) for each fishery was realized.

* From NOAA/NMFS Commercial Landings database at http://tinyurl.com/jsdyoq8

** From Table 4, Framework Adjustment 55 to the Northeast Multispecies FMP at http://tinyurl.com/zovl5lv

This is because the raison d’être of federal fishery management has become the avoidance of overfishing. Written another way, it is to have all fish stocks being managed to be at or approaching the level that will produce the maximum sustainable yield, whether they are being utilized or likely to be utilized at that level or not.

This ignores the fact that different fish species often live in very close association with each other and often behave similarly, making it difficult at best, and often impossible, to catch one species and not others. This is bycatch. It is also the root cause of the phenomena of “choke” species.

Some fish species are out there in huge numbers, some in not such huge numbers, and some are kind of rare. But as the retitled Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act (and how it is presently being interpreted) demands, each species must be managed so it will be at or approaching the level that will produce the maximum sustainable yield and each species will have a catch limit that will allow this level of catch. Obviously, rare species will have low catch limits. Not so obviously, when one of those low catch limits is reached all fishing – purposefully or inadvertently – that will catch that species must be stopped.

Thus if fish species X which is exceedingly common lives in close association with species Y which is exceedingly rare, long before the catch limit of X is reached the fishery for it will be closed because the catch limit of Y was reached.

So theoretically fifty thousand tons of haddock worth $100 million at the dock could remain uncaught because the catch limit of eight hundred tons of windowpane flounder worth $2 million or two hundred tons of ocean pout worth $1/2 million were caught. And I’ll note here that, in spite of the anti-fishing claque’s (whose members pretend that they are “marine conservationists) best efforts to convince the world that overfishing is a direct route to extinction, no fishery has ever been fished into, or even close to, extinction. An overfished fishery is simply one in which the number of fish which are left in the water can’t produce the maximum sustainable yield.

In the New England groundfish fishery, after more than a decade of intensive management and increasing enforcement, the total landings are still declining. This isn’t because there is a lack of fish available for harvest; this is because the federal legislation that controls harvesting is focused almost completely on the fish and negligibly on the fishermen. In the neighborhood of fifty thousand metric tons of haddock, twenty thousand metric tons of pollock and five thousand metric tons of redfish, easily worth one hundred million dollars to the fishermen and perhaps half a billion dollars to coastal communities) which could be sustainably harvested every year haven’t been.

(modified from http://tinyurl.com/z32qrya)

(modified from http://tinyurl.com/z32qrya)

Why is it necessary to have wolfish, ocean pout and halibut stocks at such high levels of abundance that the maximum sustainable yield can be harvested from them every year? That would be nice if it could be done without leaving a whole bunch of other fish unharvested and a whole bunch of fishermen and people in dependent businesses under- or unemployed, but that isn’t what’s happening. So our official policy is to maintain maximum population levels of these “choke” species while curtailing fishing in far more valuable fisheries and severely impacting the financial underpinnings of many of our fishing communities.

It doesn’t seem like the people in charge of policy at NOAA/NMFS are much interested in having the New England groundfish fishery (or any other) contributing as much as it could be contributing to the food supply, economy, and health of the nation. It’s apparently more important to them to wring half a million dollars a year out of some very small fisheries while foregoing tens of millions of dollars of revenues from much more robust stocks than it is to wring a quarter million dollars out of the same fisheries while deriving much greater benefits of significantly increased harvests in the larger fisheries.

So, getting back to the four sources of uncertainty above, they were obviously arrived at to help insure that too many fish aren’t harvested, that fisheries aren’t “overfished.” Why isn’t a similar effort put into a determination of the cost – the actual, real world, out of the bank accounts of fishing and fishing related businesses cost – of overfishing the so-called choke species? Or a determination of the risks – if any – involved in allowing a choke species to be overfished?

We have a twenty plus year history of observing the effects of overfishing, what’s entailed in recovering overfished fisheries, and the benefits to the fish stocks gained by having those fisheries no longer overfished. Why isn’t anything we’ve learned in these two decades or so used to give us a more realistic understanding of what “overfishing” really means to the economic viability of our domestic fish and seafood industry? Why isn’t the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, or the Pew, Packard or Allen foundations, the ENGOs they support, or the federal government funding research to determine what preventing “overfishing” is really costing?

What happens if a choke species isn’t maintained at the MSY level? Suppose ocean pout in the table above has a catch limit that is higher than the present 165 metric tons. The biomass would be reduced below the MSY level, and those fisheries that took ocean pout as bycatch or in directed fisheries would be able to catch more of their targeted species. This would cause the ocean pout stock to decline. How much should that matter? Would the cost of that decline be outweighed by the benefits to the other fisheries that ocean pout are “choking?”

The cost of requiring all species to be at the MSY level is incalculable and the benefits to the domestic fishing industry are for the most part illusory. It’s well past time for a change, a change that will let our fisheries managers get back to managing for both the fish and the fishermen.

—————————————————

For more on good (?) intentions and negative outcomes see the spiny dogfish discussion starting on the third page of the January 2015 FishNet Dogfish and seals and dolphin, oh my! (at http://tinyurl.com/h7xbbgp). When it was written the most recent Northeast Fisheries Science Center Spring Bottom Trawl Survey, done in 2013, caught 97,440 pounds of spiny dogfish. In 2015 the Spring survey caught 92,869 pounds of spiny dogfish. The same misguided management philosophy that has created choke species that limit harvesting in much more valuable fisheries is responsible for a huge biomass of a low value predatory species that is impacting the New England groundfish fishery and many others from south of Cape Hatteras into Canadian waters from “the other end.”