“Fish Wars” or a Regime Shift in Ocean Governance?

“Fish Wars” or a Regime Shift in Ocean Governance? Nils E. Stolpe

click here to visit FishNet USA

The reasons for Big Oil’s (now more accurately Big Energy’s) focus on fisheries – and on demonizing fishing and fishermen – has been fairly obvious since a coalition of fishermen and environmentalists successfully stopped energy exploration on Georges Bank in the early 80s. Using a handful of ocean oriented ENGOs as their agents, the Pew Charitable Trusts and other “charitable” trusts funded a hugely expensive campaign that the domestic fishing industry is still suffering from, but that campaign has paid off handsomely to the entities that participated in or funded it.

However, the entry of Philadelphia’s Lenfest Foundation into the fray, particularly considering that operational control was delegated to Pew, appeared to put the participation of other foundations with roots in the high tech area in a different light. Packard, Moore and Lenfest all working together with Pew et al to scuttle the public image and “revolutionize” the financial and social underpinnings of an entire industry in an apparently coordinated way started to make some sense (see http://www.savingseafood.org/opinion/nils-stolpe-on-the-consultative-group-on-biological-diversity-november-23-2009/).

But my thinking on this was further crystallized after reading a recent article in the New York Times. From the February 22,2016 Fishnet:

“The authors (of the most recent Daniel Pauly assault on commercial fishing) acknowledge, and it will probably come as no surprise to most readers, “that The Pew Charitable Trusts, Philadelphia , funded the Sea Around Us from 1999 to 2014, during which the bulk of the catch reconstruction work was performed.” However, it might be news that “since mid-2014, the Sea Around Us has been funded mainly by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.” If anyone wonders why one of the founders of Microsoft might be interested in supporting research by Daniel Pauly, from an article in the NY Times last week – Microsoft Plumbs Ocean’s Depths to Test Underwater Data Center (at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/01/technology/microsoft-plumbs-oceans-depths-to-test-underwater-data-center.html):

, funded the Sea Around Us from 1999 to 2014, during which the bulk of the catch reconstruction work was performed.” However, it might be news that “since mid-2014, the Sea Around Us has been funded mainly by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.” If anyone wonders why one of the founders of Microsoft might be interested in supporting research by Daniel Pauly, from an article in the NY Times last week – Microsoft Plumbs Ocean’s Depths to Test Underwater Data Center (at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/01/technology/microsoft-plumbs-oceans-depths-to-test-underwater-data-center.html):

“REDMOND, Wash. — Taking a page from Jules Verne, researchers at Microsoft believe the future of data centers may be under the sea. Microsoft has tested a prototype of a self-contained data center that can operate hundreds of feet below the surface of the ocean, eliminating one of the technology industry’s most expensive problems: the air-conditioning bill. Today’s data centers, which power everything from streaming video to social networking and email, contain thousands of computer servers generating lots of heat. When there is too much heat, the servers crash. Putting the gear under cold ocean water could fix the problem. It may also answer the exponentially growing energy demands of the computing world be-cause Microsoft is considering pairing the system either with a turbine or a tidal energy system to generate electricity. The effort, code-named Project Natick, might lead to strands of giant steel tubes linked by fiber optic cables placed on the seafloor. Another possibility would suspend containers shaped like jelly beans beneath the surface to capture the ocean current with turbines that generate electricity.”

Of course this needs to be coupled with Microsoft’s commitment to the future of “cloud computing” (for those readers who have successfully avoided advanced nerdhood up until now, the “cloud” is just a lot of web-connected servers housed in what are called server farms. Server farms are becoming increasingly expensive to operate shoreside – see the NY Times article linked above) and do a Google search on “Microsoft cloud future” to see where the tech industry thinks Microsoft is heading vis a vis cloud computing.

Is it possible that in the near future we’ll be reading foundation-funded research reports from our neighbors in British Columbia “proving” that submerged server farms put in place by the well-known Redmond conservationists provide much needed shelter for a myriad of marine creatures that are threatened by those rapacious fisher-men? Or that Marine Protected Areas are a really logical place to put those submerged servers?”

If you haven’t fully embraced the high-tech, internet-based wonders that are now easily and affordably available to virtually all of us – how about a Brita water purifier that will automatically order another filter before the old one needs replacing? – the major impetus for this seems to be to get folks to spend money without consciously deciding to do so. Propping this all up, making it possible, is “cloud computing” enabling you to receive a Brita filter and to get Amazon and Brita handsomely paid for getting it to you without you being involved.

With the increase in web-connected, web-enabled, web-anythinged appliances, processes, monitors, alarms, lighting and who knows what else in the future, and in hi-definition video and music streaming, a rapid growth in the capacity of the so-called cloud, which is going to become increasingly crowded, is guaranteed. That means that the demand for server farms will be increasing as well – and the closer those server farms are to the demand (population centers), the more efficient they will be.

As the Microsoft interest clearly demonstrates, alternatives to land based server farms in close proximity to population centers are going to become a high priority, and the only alternative is going to be siting them in the ocean – which offers the additional benefit of significantly reducing, or perhaps eliminating, cooling costs.

These sub-surface server farms will be as compatible with fishing as offshore power generation or the petroleum industry are. Would there be a more rational solution to what has already become a significant problem, given hundreds of billions of dollars in the bank, than for these high tech industries that are committed to a future in the oceans, than to marginalize fishermen.

And then, in what certainly fits the hackneyed term “hot off the presses,” on September 22 of this year Microsoft and Facebook announced the completion of a new submarine cable. From Barry Grossman on the Popular Mechanics website:

“Microsoft, Facebook and global telecommunication infrastructure company Telxius have completed the Marea subsea cable, the world’s most technologically advanced undersea cable. The Marea crosses the Atlantic Ocean over 17,000 feet below the ocean’s surface, connecting Virginia Beach with Bilbao, Spain.”

Finally – at least for now – we have Google – or now Alphabet, Inc., which is most known, at least in ocean circles, for its relationship with supposed ocean savior Sylvia Earle. At least back in 2010, according to Network World columnist Michael Cooney, “Google wants to control wind energy.”

From Mr. Cooney’s column:

“The project, known as the Atlantic Wind Connection (AWC) backbone will be built across 350 miles of ocean from New Jersey to Virginia and will be able to connect 6,000MW of offshore wind turbines. That’s equivalent to 60% of the wind energy that was installed in the entire country last year and enough to serve approximately 1.9 million households, Google stated.

“The AWC backbone will be built around offshore power hubs that will collect the power from multiple offshore wind farms and deliver it efficiently via sub-sea cables to the strongest, highest capacity parts of the land-based transmission system. This system will act as a superhighway for clean energy.”

Fortunately, as reported by NJ.com in 2015 (http://tinyurl.com/y7ddvmur), “with wind energy projects stalled throughout the area, this one has been put on the back burner.” New Jersey Assemblyman John Burzichelli was quoted in the article as saying of the AWC project “the will to get it done from the federal level seems to be stalled and our state BPU is distracted and we can’t get them to put it on the front burner… It’s not dead but it’s on life support.”

We can only hope that by now that life support has been terminated. Whether Alphabet Inc.’s interest in offshore, shallow-water energy development has been terminated as well is another question.

So we have a whole lot of stuff going on in the oceans, stuff that requires huge investments and stuff that a large and increasing part of the U.S. – and the world’s – economy is based on. It’s difficult to consider any of this without questioning how Microsoft and Facebook and Amazon and a slew of other multi-national mega (and not so mega) corporations intend to protect these investments. And, unlike on land, security is a whole different matter when coastal waters are involved, and the complexity (and the potential for “differences of opinion” and misunderstandings) increases tremendously offshore in international waters. It’s questionable that any corporation, no matter how mega, would be eager to get involved in securing their inshore or offshore investments.

Last week Johan Bergas, Senior Director of Public Policy at Paul Allen’s Vulcan Inc (from Wikipedia “Vulcan Inc. is a private company founded by philanthropist and investor Paul Allen. It was established in 1986 and oversees Allen’s diverse business activities and philanthropic endeavors….”) and retired admiral and Chairman of the Board of the U.S. Naval Institute James G. Stavridis had a column in the September 14 Washington Post titled The Fishing Wars Are Coming. The column was a justification for the militarization of fisheries enforcement as a way to stave o ff the supposedly inevitable international conflicts brought about by future “fish wars.”

ff the supposedly inevitable international conflicts brought about by future “fish wars.”

For some unfathomable reason the two authors neglected to mention that international disputes over fishing rights are hardly new phenomena and fishing wars have come and gone for centuries. While they attempt to make fish wars the latest threat to international political stability, that’s about as inaccurate as a forecast can be.

For those readers who aren’t that well versed in the history of fishing, the so called Cod Wars, running from the 1950s to the 70s, were a series of disputes between Britain and Iceland over who got to fish in Icelandic waters (http://britishseafishing.co.uk/the-cod-wars/).

But the Cod Wars had roots extending much farther back. In the last century, “in April 1899 the steam trawler Caspian was fishing off the Faroe Islands when a Danish gunboat tried to arrest her for allegedly fishing illegally inside the limits. The trawler refused to stop and was fired upon, first with blank shells and then with live ammunition. Eventually the trawler was caught, but before the skipper, Charles Henry Johnson, left his ship to go aboard the Danish gunboat, he ordered the mate to make a dash for it after he went on to the Danish ship. The Caspian set off at full speed. The gunboat fired several shots at the unarmed boat but could not catch up with the trawler, which returned heavily damaged to Grimsby, England. On board the Danish gunboat, the skipper of the Caspian was lashed to the mast. A court held at Thorshavn convicted him on several counts, including illegal fishing and attempted assault, and he was jailed for thirty days.” (Bale, B., 2010, Memories of the Lincolnshire Fishing Industry, Countryside Books pg. 35.)

A little later we have “no more vexatious international entanglement could well be imagined than the present fishery dispute between Newfoundland and the United States. While, superficially, it appears to be a mere question of whether the Colonial Government can hamper American fishermen in procuring cargoes of herring on the West Coast of the Island, it really comprehends the genesis of the dispute between the Republic and Canada respecting the whole Atlantic Fisheries, which has proved so difficult of solution during the past fifty years. A close study of the subject shows it to be fraught with serious problems and complicated offshoots, and to bristle with issues demanding the subtlest reasoning and most cautious presentments by jurists and state.” (1906, McGrath, P.T., The Newfoundland Fishery Dispute, The North American Review, Vol. 183, No. 604, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25105716.pdf?refreqid =excelsior%3A50c1e52aa484cac4fe652ccd1b0f1042).

And in 1911 T.W. Fulton published The sovereignty of the sea: an historical account of the claims of England to the dominion of the British seas, and of the evolution of the territorial waters : with special reference to the rights of the fishing and the naval salute. In it he wrote “the Scandinavian claims to maritime dominion are probably indeed the most important in history. They led to several wars; they were the cause of many international treaties and of innumerable disputes about fishery, trading, and navigation; they were the last to be abandoned. Until about half a century ago Denmark still exacted a toll from ships passing through the Sound, a tribute which at one time was a heavy burden on the trade to and from the Baltic. Still more extensive were the claims put forward by Spain and Portugal. In the sixteenth cen-tury these Powers, in virtue of Bulls of the Pope and the Treaty of Tordesillas, divided the great oceans between them. Spain claimed the exclusive right of navigation in the western portion of the Atlantic, in the Gulf of Mexico, and in the Pacific. Portugal assumed a similar right in the Atlantic south of Morocco and in the Indian Ocean. It was those preposterous pretensions to the dominion of the immense waters of the globe that caused the great juridical controversies regarding mare clausum and mare liberum, from which modern international law took its rise.” https://archive.org/details/sovereigntyofsea00fultuoft.

In this context it’s hard to understand how Bergas and Stavridis could write “that lawmakers are finally catching up to something that the Navy and Coast Guard have known for a long time: The escalating conflict over fishing could lead to a ‘global fish war.’ This week, as part of the pending National Defense Authorization Act, Congress asked the Navy to help fight illegal fishing. This is an important step. Greater military and diplomatic efforts must follow. Indeed, history is full of natural-resource wars, including over sugar, spices, textiles, minerals, opium and oil. Looking at current dynamics, fish scarcity could be the next catalyst.” Or how they could omit fish from their list of “natural-resources wars.”

It’s kind of easy to imagine a retired admiral of a certain stripe engaging in saber-rattling over a perceived imminent threat to the sovereignty of the seas.

But why the interest in this issue by Andrus, Inc., founded and (I presume) controlled by one of the mega-rich founders of Microsoft? And why the interest in other ocean- and fishing-related issues by other luminaries of the hi-tech firmament?

(Perhaps not as an aside, the Washington Post is owned by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. Amazon and Microsoft are two of the largest providers of “cloud” services.)

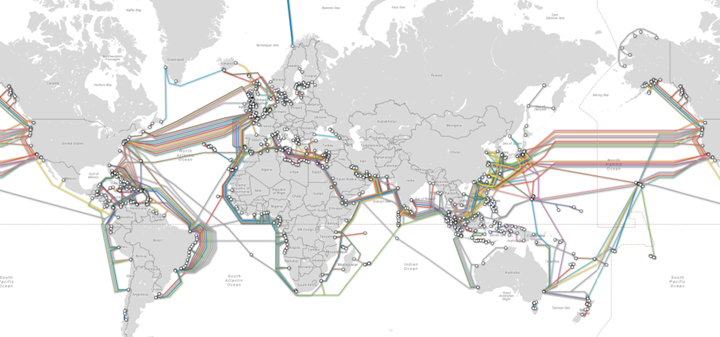

Bergas and Stavridis finish with “this week, as part of the pending National Defense Authorization Act, Congress asked the Navy to help fight illegal fishing. This is an important step. Greater military and diplomatic efforts must follow.” But they don’t qualify their “illegal fishing.” Most readers will automatically assume that they are referring to the illegal fishing that is supposedly happening on the high seas, in international waters and beyond the reach of our Coast Guard – predictably with a focus on China. But is that necessarily the case? “Illegal fishing” also includes a family catching clams on Sunday, a recreational angler keeping a striped bass that is a half an inch too short or too long, a commercial fisherman transiting – not fishing in – a particular area with the wrong net on board and seemingly uncountable ways for people to catch or to attempt to catch fish. What are the odds that it will also include any fishing vessel getting too close to offshore “windmills” or threatening submarine cables in the not too distant future? (Below is “a map of the world’s submarine cables” from Bob Dorman’s article How the Internet works: Submarine fiber, brains in jars, and coaxial cables posted to the ARS Technica website in May of last year – available at https://tinyurl.com/kth7g24).

Obviously many of these cables (and prospective wind generators and sub surface server farms) are or are going to be where fishermen fish. It’s axiomatic that much of the world’s fishing happens adjacent to where much of the world’s population lives – particularly those members of the world’s population who can afford relatively expensive protein from the sea. It’s equally obvious that most of those internet cables and other barriers to fishing are going to places where there are concentrations of people who can afford, and who in fact demand, state-of-the-art telecommunications access and dependable electricity. And to get them there some of their susceptible infrastructure will have to be sited in relatively shallow areas – where most of the worlds fish and shellfish are live and where most fishermen fish.

If you don’t see any problems developing here, I’ll refer you to The International Cable Protection Committee’s Fishing And Submarine Cables – Working Together, which can be downloaded via the ICPC Publications page at https://www.iscpc.org/publications/.

Like the failed attempts to raise the world’s concern about so-called seafood slavery a few years back, full of “sound and fury” but signifying not much at all, this is all part and parcel of what appears to be a well-coordinated and a frighteningly well-funded campaign to further marginalize fishermen, who seem to have this belief that they need to fish where the fish are, not where the big-time ocean exploiters want them to fish.

So the multi-billion dollar multinational tech giants have collectively invested billions in what, at least from the outside, makes it appears as if their next frontier isn’t Gene Rodenberry’s space, but those nearshore waters that have supported the world’s fishermen, and a big part of the world’s population, for quite some time. All of the foregoing makes one wonder who will own – or control – the world’s oceans, and what fishing remains possible – or legal – in the coming years.

_________________________

And, lest anyone is inclined to forget the folks at Pew and their efforts….

From an email message by Pew Oceana staffer Lora Snyder dated September 18, 2017:

“Tell Congress: Don’t gut our key fisheries law. Our oceans and marine life need your help, immediately. There is a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives that would undermine and undo years of successful work to manage the health of America’s fisheries. We must speak out now against this anti-science bill before sharks, fish and many other marine animals suffer the consequences. Tell your representative to protect our oceans, at-risk species, fisheries, and the communities that rely on them.”

I won’t comment here on Ms.Snyder’s/Pew Oceana’s contention that Congressman Young’s legislation which would return sorely needed flexibility to federal fisheries management would “gut” the Magnuson-Stevens Act. In my last FishNet (http://www.fishnet-usa.com/MagnusonReauthorization_2017.pdf) I quoted from the Senate Testimony of Chris Oliver, the head of the National Marine Fisheries Service and until a couple of months ago the Executive Director of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, and John Quinn, the Chairman in the New England Fishery Management Council and of the Council Coordinating Committee – made up of Regional Fishery Management Council leadership. To suggest that these two individuals – and the groups they have represented or are currently representing would support “an anti-science bill” might be a record in stretching credulity, even for Pew/Oceana.

What I will comment on is Ms. Snyder’s – or her editor’s/overseer’s – ability to make a mistake that most advanced secondary school students with even a superficial interest in our oceans and the creatures in them wouldn’t. In spite of what Ms. Snyder wrote “to save our oceans,” sharks are actually real, genuine fish. They aren’t bony fish (Osteicthyes) but, having – along with skates, rays and a few other groups of fish – cartilaginous skeletons, are in the class Chondricthyes. But they are emphatically fish. Just ask anyone, at least anyone who isn’t employed by Pew/Oceana.

It’s hard for me to imagine any sentence more “anti-science” than Ms. Snyder’s “we must speak out now against this anti-science bill before sharks, fish and many other marine animals suffer the consequences.” And yet someone who is capable of such a gross scientific blunder feels free to question the judgment of Chris Oliver, John Quinn and a large portion of the domestic fishing industry and to presume that the future of the oceans is in her hands. World-class hubris has surely found a home at Pew/Oceana!