Blame it all on what we’re catching! By Nils E. Stolpe

FishNet-USA/04/01/06 – The entire focus of what is considered fisheries management today is on first blaming (generally commercial) fishing for any situation involving the perception that there are not enough fish, and then controlling (generally commercial) fishing to return a population of fish to what is presumed to be some optimum level. And most recently this has even been extended to restoring once healthy habitat that has been supposedly compromised by (generally commercial) fishing.

Why this focus on fishing? The logical answer would seem to involve an old adage dealing with smoke and fire. Is that necessarily so, or are there other factors at work instead?

A very brief history of wildlife management in general

Even before we in the colonies were attempting to hunt bison and passenger pigeons and anything else that was fit to eat or wear or shoot into extinction, the folks in Europe were realizing that such a strategy didn’t bode well for the future of small furry and finny creatures. Accordingly, the creatures were all claimed by members of the aristocracy, who proceeded to manage them (or more correctly, to have them managed) on their estates and on public lands. Needless to say, this was a fairly simple undertaking, aimed at controlling fairly simple and fairly artificial systems to “sustainably” produce a handful of desirable critters for the lords and ladies of the manor and their guests to eat or catch or shoot. Apply a few simple rules – don’t shoot too much, don’t catch too much and keep the peasants out – and you’d be in business for decades. This was because there were few factors affecting the highly controlled forests or lakes or rivers other than harvesting.

Moving forward – or perhaps not, at least as far as effectively managing fisheries was concerned – a few hundred years, in a lecture given at the Fisheries Centennial Celebration in 1985 (The Historical Development of Fisheries Science and Management, http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/

Royce followed this with “the dry wit of Milton C. James, who for many years was the Assistant Director for Fisheries of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is as pertinent today as it was in 1950 when he made that statement at the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Conference.” We agree with Royce completely here, but probably not for the same reasoning. What James wrote wasn’t pertinent in 1951, it wasn’t pertinent in 1985 and it isn’t pertinent today. At least back in 1951 we didn’t know any better, but by 1985 it should have been obvious that there were many other factors, both man-caused and natural, that affected our fish stocks.

Have we grown out of it?

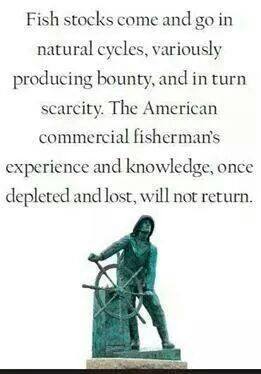

A rational and well-informed person, one who was familiar with the advances that have been made in the last half a century in understanding ecosystems, how they function and what our effects on them are, would assume that fisheries management had gotten beyond the simplistic view that (mostly commercial) fishing was invariably the major determinant of the health of fish stocks. With increasing knowledge of the downstream impacts of what goes on upstream, with the detection of various chemical pollutants in marine organisms far removed from any identifiable source, with the identification of weather/climate cycles and the attendant regime shifts that they bring about, and with a realistic grasp of the importance of wetlands and estuaries to inshore and near shore fisheries, it’s hard to imagine that we haven’t moved beyond the “blame it all on fishing” paradigm.

Unfortunately, the belief that if you can limit fishing you’ll be able to protect the fish is still at play in marine fisheries management today. In spite of the fact that estuaries and oceans are tremendously complex systems affected by myriad natural and anthropogenic activities, our fisheries management system is still based on controlling the fishery by controlling the harvest.

This is most convincingly demonstrated by the fact that in fisheries management only two sources of mortality are recognized. One of these is – you guessed it! – fishing mortality. The other is termed natural mortality, though it is defined as “that component of total mortality not caused by fishing, but by natural causes such as predation, diseases, senility, pollution, etc.1”

“Refining” this definition of natural mortality, we have from NMFS “that part of total mortality applying to a fish population that is caused by factors other than fishing. It is common practice to consider all sources together since they usually account for much less than fishing mortality.2” While it’s kind of hard to imagine that fishing is “usually” the major cause of mortality in a fish population (of all of the hundreds or thousands or millions of eggs that a fish produces each year, a very, very small proportion survive to be caught by fishermen), and while it’s guaranteed to skew every discussion of mortality in fisheries against fishing, that’s the official government position.

Note that pollution is considered a part of natural mortality, as are any other anthropogenic effects other than fishing. We’ll get back to that later, but for now, consider the ramifications of recognizing only two sources of mortality, one “natural” and the other caused by fishing, when dealing with a fish population.

It’s been ingrained in modern society that anything that is “natural” is considered to be good and desirable, and woe to anyone who would dare to trifle with the natural order of things. Who could forget the “it’s not good to fool Mother Nature” margarine commercials of a few years back? Of course, the average person doesn’t have any idea that when it comes to fisheries management, mortality brought about by pollution, in fact mortality brought about by anything other than fishing, is considered “natural,” and is automatically considered “good,” leaving fishing as the only “unnatural” factor affecting fish stocks.

Is this the wrong way to manage?

If commercial fishing were the only, or even the predominant, source of mortality impacting a fish stock, then no one could argue that focusing on managing commercial fishing wouldn’t be the most effective way of managing it. On the other hand, it seems equally inarguable that if commercial fishing weren’t the only or the predominant source of mortality, then to focus solely on commercial fishing wouldn’t be effective. Rather, such a focus would be a virtual guarantee that commercial fishing on that stock would be “managed” into oblivion.

As evidenced by commercial fishery after commercial fishery enduring ever-increasing restrictions for year after year with no relief in sight, managing fish stocks by relentlessly cutting back on commercial fishing effort isn’t working the way it’s supposed to be. The anti-fishing activists blame this on a fishery management system that is compromised by conflicts of interest and is therefore unwilling or unable to impose the strong medicine that, in their estimation, curing our fisheries requires. Accordingly, they are in the midst of a campaign to amend the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act to remove the slight bit of flexibility from the management process that at this point is the only thing allowing a number of commercial fisheries to survive.

But what if there are factors at work on particular fish stocks, factors that would be considered “natural” by the fisheries managers and thus unworthy of their attention, that are significantly influencing the health of those stocks?

A major “natural” source of mortality

We’ll start with the easiest and most understandable factor with the potential to significantly affect our fisheries, human population growth on the coasts, or more precisely, the impact of that growth on the productivity of inshore and near shore waters. If you’ve bought into the fisheries managers’ vocabulary, this is a “natural” source of fish mortality that is insignificant when compared to fishing mortality. But is it?

In the U.S. the population on the coasts has been and continues to increase at a greater rate than the general population. This is a worldwide trend. Every year there are more people, and every year more of them are living on the coasts.

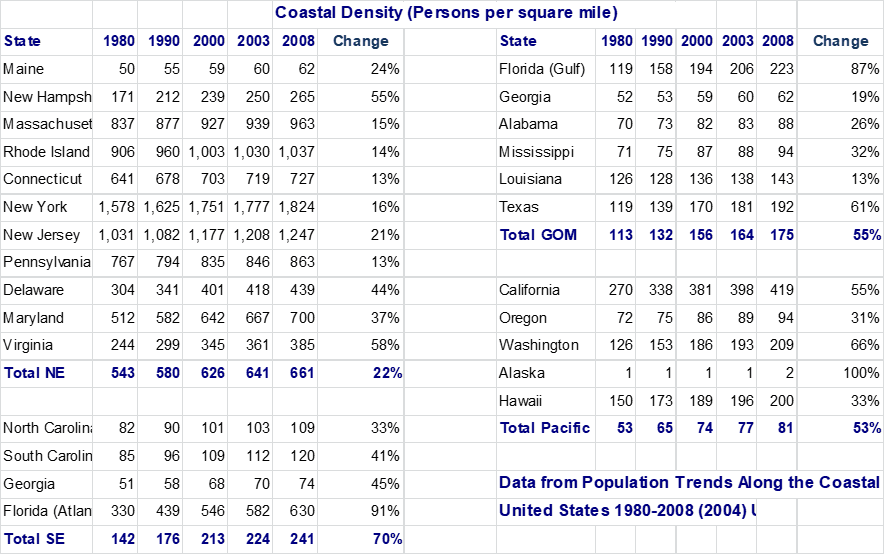

Crossett, Culliton, Wiley and Goodspeed (2004, Population Trends Along the Coastal United States: 1980-2008, US Dept. Of Commerce/National Ocean Service) document the dramatic increase in population in coastal counties in the U.S. from 1980 to 2000. The only state that didn’t experience a significant increase in its coastal population density during this period was Alaska. Regionally, the coastal population density increased 18% in the Northeast, 58% in the Southeast, 45% along the Gulf coast and 45% for the Pacific states (including Alaska and Hawaii).

This coastal population explosion is unquestionably accompanied by increases in non-point source pollution, in recreational boating, in harmful algal blooms and so-called dead zones3, in the loss of productive wetlands, in the amount of household chemicals and pharmaceutical “residues” making their ways into coastal waters, in the amount of impervious ground cover and the corresponding increase in water borne sediments, with a host of side effects with the demonstrated potential to directly or indirectly impact the health of fish stocks.

In the U.S. “five of the 10 most populated watersheds are located from southern Virginia to New England. The Hudson River/Raritan Bay and Chesapeake Bay watersheds were the most populated overall, with over 13 million and 10 million people, respectively.” (from Crossett, Culliton, Wiley and Goodspeed). We’re not making much of a leap when we assume that this coastal population increase has had negative impacts on inshore and near shore water, nor that there would be an accompanying effect on the resident and migratory fish stocks.

How does this apply to New England Groundfish?

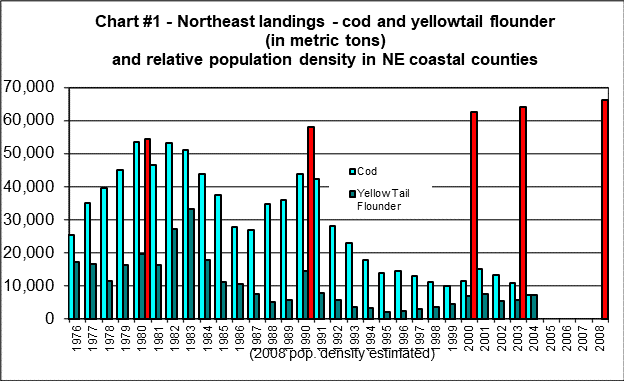

With cut after cut being inflicted on the groundfish fleet, there still aren’t enough fish – at this point cod and yellowtail flounder in particular – to meet the rigid “rebuilding schedules” imposed after the passage of the Sustainable Fisheries Act. Under the latest management proposal, boats are to be allowed on the order of twenty days a year to fish for groundfish. The fleet average in the ‘70s and early ‘80s was perhaps 200 to 250 days. The proposed cuts represent a reduction of perhaps 90% in fishing time per vessel over several decades (without even taking into consideration what have been significant reductions in the fleet size). As Chart #1 indicates, since the passage of the Magnuson Act in 1976, the landings of these two species have declined dramatically in spite of the drastic and ongoing reductions in fishing effort.

This isn’t just characteristic of the cod and yellowtail flounder fisheries. In Chart #2, landings of the various species that make up the groundfish complex are depicted. In all of them fishing effort has being ratcheted downwards continuously (the increase starting in the late 1970s was an artifact of the passage of the Magnuson Act in 1976). Looking at this chart, it’s awfully difficult to believe that, along with fishing, there aren’t other factors influencing the stocks. If not, with such drastic reductions in fishing effort as the landings data indicate, why haven’t a greater proportion of the stocks recovered? At the same time, the coastal population in the Northeast continues to increase – as does the loss of wetlands, the amount of non-point source pollution, the recreational use of our waterways, etc. The attendant and undoubtedly increasing impacts on the fisheries, because they are considered to be part of the “natural” mortality and because the focus of fisheries management has always been on fishing, escape the managers’ scrutiny and the public’s attention while the groundfish industry faces cutback after cutback with no sign that relief is on the way. (For another example of this total focus on fishing, see “Brief history of the groundfishing industry of New England” on the Northeastern Fisheries Science Center website at http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/history/stories/groundfish/grndfsh2.html).

If we assume that there are other factors that are negatively impacting the groundfish stocks, and if the fisheries managers continue to reduce fishing effort in a futile attempt to counteract them, what lies ahead for the New England groundfish industry?

The Chesapeake Bay

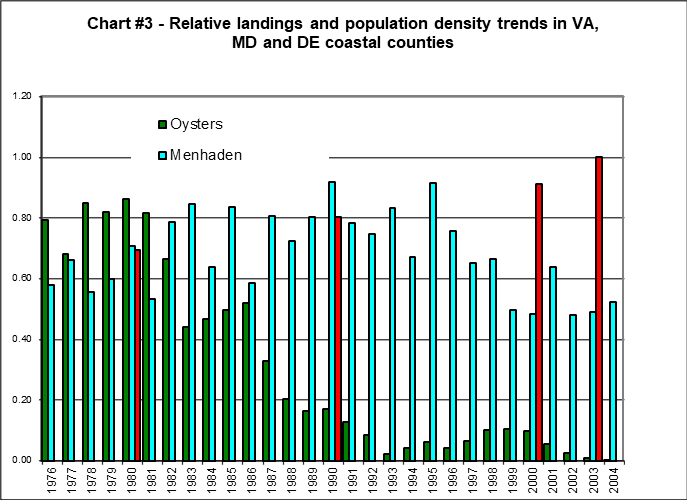

In spite of this, there has been a recent movement to blame the ills of the Chesapeake on the overharvest of two filter-feeding commercial species, oysters and menhaden. Landings in both of these fisheries have declined significantly in the Chesapeake in recent decades. As shown in Chart #3 below, menhaden landings have been declining for well over a decade and oyster landings since the 1950s. The menhaden fishery is not being overfished, though there are recognized problems with recruitment (the addition of young fish to the stock). The view being pushed by anti-fishing groups is that decline in the productivity of the Chesapeake isn’t responsible for the decline in these fisheries but vice versa. Understandably, some of the most vehement critics of the Virginia and Maryland commercial fisheries are among those 16 million people who live around, play on and flush into the Bay. Their endeavors on behalf of the Chesapeake would be far more effective if each of them, in company with a dozen or so neighbors, packed up and moved to North Dakota.

The one fisheries “success story” in the Chesapeake – the resurgence of the striped bass population – has been tarnished by recent reports that a large part of the population has been afflicted with mycobacteriosis a lethal bacterial disease that has been increasing in the Bay’s striped bass for at least a decade.5 Mycobacteriosis is linked to degraded water quality.

The situation regarding coastal development in Alaska is unique. With such a sparsely populated coastline, it’s hard to imagine that there are any impacts from coastal development, and though the coastal population density has increased slightly, according to the U.S.D.O.C. it won’t reach two people per square mile until 2008 (the following chart lists the state-by-state coastal population density). This is in strong contrast to the other coastal states, with coastal population densities ranging from 60 people per square mile (Maine and Georgia) to 1,777 (New York). While Alaska’s fisheries are considered to be among the world’s most well managed, as they rightfully should be, isn’t there another message in there as well? Why is managing fishing mortality effective in managing Alaska’s fisheries while it’s for the most part inadequate in other fisheries? New England and the Chesapeake Bay estuary are in no way unique. In fishery after fishery and for year after year, commercial fishing effort is reduced because fisheries management is all about reducing fishing mortality and not about much else. And while fishing effort is continuously reduced, the coastal population continues to climb and the attendant “natural” mortality continues to increase.

And Natural cycles in fish populations

Some fish stocks vary cyclically. Among the most well-known examples of this are the extremes exhibited by west coast sardine/anchovy stocks. Sardines off California go through a “boom or bust” cycle, to be replaced by anchovies as their populations plummet. This cycle, which was responsible for the collapse of the sardine fishery that had supported Cannery Row in Monterey, is driven by changes in oceanographic conditions brought about by a short-term “climatic” cycle of a 50 to 60 year duration and has been tracked back several thousand years.6

Related to the El Niño cycle and other factors, regime shifts in the Pacific drive periodic fluctuations in fish stocks. While research is not as well advanced, regime shifts are at work on fisheries in the Atlantic as well.7,8

One might argue that, in the face of declining fish stocks, rational fisheries management would demand a reduction in fishing effort, and in some instances that’s surely the case. But one could just as well, and more convincingly argue, that in rational fisheries management all sources of mortality should be identified and quantified and, to the extent possible, controlled. That should be one of the primary underpinnings of ecosystem management, but it isn’t happening. According to the management establishment, it’s only about fishing. Our fishermen and our fish are paying the price.

1 http://www.fishbase.org/

2 http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/

3 http://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/

4 http://erf.org/user-cgi/

5 http://www.dnr.state.md.us/

6 http://news.

7 http://www.ices.dk/iceswork/