NOAA Fisheries Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update

Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet USA

© 2020 Nils E. Stolpe

August 31, 2020

NOAA Fisheries Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update

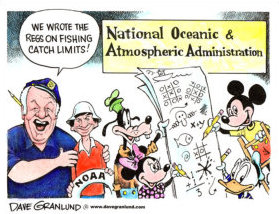

Well, first we have this reassuring (at least if you’re not that familiar with the capacity of NOAA Fisheries to get it really, really wrong!) statement that “NOAA Fisheries is actively monitoring and adjusting to the COVID-19 national health crisis” (https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/noaa-fisheries-coronavirus-covid-19-update). Nothing to worry about, right? Well, not quite nothing. While I’ve seen nothing official, word on (at least some of the New Jersey) docks is that, in spite of the ongoing and very possibly worsening national Covid-19 health crisis, the mandatory on-board observers are back in force and demanding rides.

A few FishNet issues back I wrote about NOAA Fisheries (used to be National Marine Fisheries Service. It’s still the same people and the same institutional hang-ups) cancelling research cruises by the NOAA “Navy” which, up until the pandemic crisis, were carrying out surveys that were a supposedly critical part of the agency’s fisheries management mission. Apparently those particular surveys weren’t so critical after all.

To date those cancelled “critical” NOAA surveys are:

NOAA Fisheries will Cancel Five Alaska Research Surveys for 2020

Announcement of survey cancellations in 2020.

NOAA Fisheries Cancels Four Fisheries and Ecosystem Surveys for 2020

The Summer Ecosystem Monitoring, Northern Shrimp, Autumn Bottom-Trawl, and Summer/Fall Plankton surveys have been cancelled for 2020.

NOAA Fisheries Cancels Three West Coast Surveys for 2020

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/agency-statement/noaa-fisheries-cancels-three-west-coast-surveys-2020

The Groundfish Bottom Trawl Survey, California Current Hake Research Cruise, and California Current Ecosystem Survey have been cancelled for 2020.

NOAA Fisheries Cancels Remaining Hawaiian Islands Surveys for 2020

The annual Hawaiian monk seal and sea turtle field season deployment, a portion of the main Hawaiian Islands bottomfish survey, and the main Hawaiian Islands corals assessment are cancelled for 2020.

NOAA Fisheries Cancels 2020 Southern California Shelf Rockfish Hook and Line Survey

The Hook and Line (H&L) Survey has been cancelled for 2020.

(Note that while I don’t have any idea if this list represents the sum total of NOAA Fisheries cancelled research surveys or not, I do know that the cancelled cruises represent many millions of taxpayer dollars tied up at the dock – and incurring even more significant maintenance costs while tied up).

In addition, NOAA/NMFS offices are closed to outsiders and meetings/hearings and other official activities have either been cancelled or have been reorganized to be Covid-19 compliant. For examples see the New England Fisheries Management Council’s plans for a hearing on Groundfish Monitoring Amendment 23 (at https://tinyurl.com/y5m9fkub) and the notice of cancellation (excerpted below) of the annual citizen scientist beluga whale census for 2020 at https://tinyurl.com/y497wv4p).

Given the continued uncertainty around travel restrictions and the expected continued need for social distancing, our annual Belugas Count! event, scheduled for September 19, 2020 has been canceled. We hope to see you all in September 2021.

If you decide to venture out along Cook Inlet on your own please follow the current state and local health mandates.

If you happen to observe beluga whales incidental to your adventures please report them to the Cook Inlet Beluga Whale Photo ID Project.

Every sighting counts but above all else please keep your loved ones and community safe.”

It seems like just about anything that might involve NOAA/NMFS employee exposure to Covid-19 has either been cancelled or public participation has been severely restricted or eliminated.

What about cruise ships operations that earned so much media attention this past spring?

Wikipedia lists 54 cruise ships which have had “confirmed positive cases” of Covid 19 reported. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_on_cruise_ships).

From the CDC’s role in helping cruise ship travelers during the COVID-19 pandemic (https://tinyurl.com/vpfoamv)

What is the No Sail Order?

In response to the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic and the increased risk of spread of COVID-19 on cruise ships, CDC published the first industry-wide No Sail Order on March 14 to prevent, among other things, new passengers from boarding cruise ships. CDC extended its No Sail Order, effective April 15, 2020, to continue to suspend all cruise ship operations in waters subject to US jurisdiction. Among other things, cruise lines are required to develop comprehensive plans to prevent, detect, respond to, and contain COVID-19 on their cruise ships to protect the health and safety of both passengers and crew. CDC extended its No Sail Order a second time, effective July 16, 2020. Among other things, passenger operations remain suspended; cruise ship operators must continue to follow CDC’s Interim Guidance for Mitigation of COVID-19 Among Cruise Ship Crew During the Period of the No Sail Order; and cruise ship operators with appropriate No Sail Order response plans must continue to follow the COVID-19 Color Coding System, which requires preventive measures for crew onboard based on the ship’s status.

And the Navy?

Wikipedia lists 22 naval vessels worldwide with reported cases of Covid 19 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_on_naval_ships)

Then there’s Captain of aircraft carrier with growing coronavirus outbreak pleads for help from Navy (San Francisco Chronicle/Gafni, M. and J. Garofoli/March 31, 2020 Updated: June 8, 2020 2:07 p.m. https://tinyurl.com/qkqua59):

“The captain of a nuclear aircraft carrier with more than 100 sailors infected with the coronavirus pleaded Monday with U.S. Navy officials for resources to allow isolation of his entire crew and avoid possible deaths in a situation he described as quickly deteriorating.

The unusual plea from Capt. Brett Crozier, a Santa Rosa native, came in a letter obtained exclusively by The Chronicle and confirmed by a senior officer on board the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt, which has been docked in Guam following a COVID-19 outbreak among the crew of more than 4,000 less than a week ago.”

Unfortunately, and in spite of the extreme (and admirable) caution that the people at the top of NOAA/NMFS and others that are charged with the safety of people aboard U.S. military and commercial vessels have demonstrated in protecting their own officers, crews and members of the public from exposure to Covid-19, that level of caution is not applicable to the captains/crew of commercial fishing vessels. They are still in the precarious position of having to take aboard federal observers (either NOAA/NMFS employees or employees of a handful of firms who have contracted with NOAA/NMFS to supply them).

Note – the following discussion depends to a great extent on the fact that we are far from having a full understanding of how Covid-19 is spread from person to person. One of the things that we don’t understand is how long it takes after exposure to Covid-19 virus particles before a person becomes infected. We also don’t know how much exposure to Covid-19 it takes – both time-wise and level-wise – for an infected person to be contagious (or if he or she must be infected or just exposed to be a contagious). Is it ten minutes and a sneeze from 5 feet away? Is it three days of breathing in one another’s face without a surgical mask? Is it two hours at a demonstration, a campaign rally or a concert? How effective are social distancing or masks? Can you catch it by pumping your own gas after someone who is contagious used the pump? By drinking a glass of soda or beer that was poured by a contagious person? By typing your pass code into a public keypad after someone who is contagious used it?

We also don’t know whether (or for how long) Covid-19 viral particles left by someone who is contagious on what kind of surfaces exposed to what conditions can infect someone who contacts those surfaces.

What we do know is that someone can be symptom-free (asymptomatic) and still be contagious. For all we know at this point, someone can be infected by the most casual interaction with someone who is asymptomatic and yet is infectious. Probability –and common sense – argues against that, but is that good enough? Not for me, so for the past five or six months I have been avoiding unnecessary interactions with other folks as much as is humanly possible.

And to add to what we now know but didn’t know last week, and to add to the general lack of knowledge of (or confusion about) what’s going on vis à vis Covid-19 testing:

Breaking – but not really surprising – News:

(CNN at https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/26/health/cdc-guidelines-coronavirus-testing/index.html) The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has changed its Covid-19 testing guidelines. The agency no longer recommends testing for most people without symptoms, even if they’ve been in close contact with someone known to have the virus.

Previously, the CDC said viral testing was appropriate for people with recent or suspected exposure, even if they were asymptomatic.

Here’s what the CDC website said previously: “Testing is recommended for all close contacts of persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Because of the potential for asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission, it is important that contacts of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection be quickly identified and tested.”

The CDC changed the site on Monday. Here’s what it says now: “If you have been in close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with a COVID-19 infection for at least 15 minutes but do not have symptoms, you do not necessarily need a test unless you are a vulnerable individual or your health care provider or State or local public health officials recommend you take one.”

Those who don’t have Covid-19 symptoms and haven’t been in close contact with someone with a known infection do not need a test, the updated guidelines say.

“Not everyone needs to be tested,” the agency’s website says. “If you do get tested, you should self-quarantine/isolate at home pending test results and follow the advice of your health care provider or a public health professional.”

It’s important to note here that according to the CDC “if you have been in close contact (within 6 feet) of a person with a COVID-19 infection for at least 15 minutes but do not have symptoms, you do not necessarily need a test…” However, we do know that a large percentage of Covid-19 carriers are asymptomatic. Perhaps the CDC believes that if you have had close contact (less than 6 feet) with a possible spreader (it seems to me that that could be just about anybody) for more than 15 minutes you should flip a coin, have your tea leaves read, or stand on your head and spin around four times before contacting your own doctor or another bureaucrat for advice and guidance.

When in doubt, lock ‘em in or out?

It’s comforting to know that the Navy and federal agencies are concerned with their employees, officers, crew and paying passengers on commercial and/or military vessels. While no one has made it “official,” it seems pretty obvious that if you spend any amount of time in close proximity to anyone who has been in contact with anyone else (or maybe with a contaminated surface) in the last two weeks that there is a chance that they could be a Covid-19 carrier, whether they are exhibiting any symptoms or not.

But NOAA/NMFS and/or the contracting observer providers want us to believe that have a handle on the whole thing?

Let’s suppose that you are the Captain or a member of the crew of a commercial fishing vessel at the dock and preparing to cast of for a fishing trip, and suppose that a stranger approaches you, presents some identification showing that he or she is a vessel observer working for a NOAA/NMFS contractor and has met all of the “Official” requirements to safely board your vessel and perform all necessary operations with you and your crew for the duration of the trip. We’ll assume that the “requirements” are that he or she is asymptomatic and that she or he has self-quarantined for a specified period. Does “asymptomatic” mean that she or he does not have Covid-19? No. Does having been “self-quarantined” for a specified time mean that he or she does not have Covid-19 or is not contagious? Where was she or he quarantined? Who did he or she come in close contact (for simplicity’s sake we’ll assume closer than 6 feet for longer than 15 minutes, but that’s certainly not carved in stone) with during the quarantine? And what did she or he do when travelling from the quarantine site to your vessel? How many people were contacted? Were they wearing protective gear? Were they more than 6 feet away? On the journey to your boat how many surfaces were touched since the last time they were disinfected?

I’d guess that NOAA/NMFS and/or the contracting company will assure you that allowing the observer on board is safe. That being the case, NOAA/NMFS and/or the contracting company should be willing to accept all Covid-19 related responsibility for their observers. But I’ll bet they won’t. If they don’t, that responsibility in all likelihood will end up on the Captain’s/owner’s shoulders. And that responsibility might well extend through several generations back in port and in the community.

Without indemnification by NOAA/NMFS or the contracting observer companies, the vessel captain/owner could have significant “downstream liability.” Though it is promotional in nature, the following excerpt from a local law firm’s website (The Barns Trail Group, a Tampa, FL law firm at https://tinyurl.com/y57zu9et) lays it out fairly simply. A disclaimer here: there’s not much that’s simple in maritime law.

Civil liability

Under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), boat owners of seagoing vessels, including inland waterways, are required by law to ensure that all crew and passengers onboard are aware of safety management procedures, drafted under the provisions of the International Safety Management (ISM) code.

SOLAS holds vessel owners liable for civil litigation in the event of personal injury, wrongful death and other claims for financial damages if the captain fails to meet his or her legal responsibility. This covers charter tour boats and privately-held yachts, as well as cruise liners.

Injured parties may certainly have the right to sue for damages against the boat owner under international maritime law, but may also be able to “pierce the corporate veil” and sue the captain and individual crew members for failing to meet their responsibilities under SOLAS, as well.

If it can be demonstrated through evidence that the captain failed to meet the legal responsibility to put passenger safety above his or her own safety, civil damages may be possible for negligence.

A final point

For over two decades fisheries scientists, managers, statisticians and technologists have been working on developing automated systems which would log with acceptable accuracy interactions between marine organisms and fishermen. This would obviate the necessity of on-board observers, who at the best of times come with an almost overwhelming plethora of problems. I think I can say without fear of contradiction that these are far from the best of times. I think the last few thousands of words that I have written in FishNet USA, other writers have written elsewhere, and that a whole bunch of fishermen and other commercial fishing industry members, their friends and their families will attest to, with the current Covid-19 crisis that plethora of problems has made it over the top and is now solidly in the realm of the insurmountable.

On electronic monitoring

Since the beginning of the 21st century, electronic monitoring (EM) has emerged as a cost‐efficient supplement to existing catch monitoring programmes in fisheries. An EM system consists of various activity sensors and cameras positioned on vessels to remotely record fishing activity and catches. The first objective of this review was to describe the state of play of EM in fisheries worldwide and to present the insights gained on this technology based on 100 EM trials and 12 fully implemented programmes. Despite its advantages, and its global use for monitoring, progresses in implementation in some important fishing regions are slow. From the abstract: van Helmond et al. Electronic monitoring in fisheries: Lessons from global experiences and future opportunities. Fish and Fisheries. 2020;21:162–189.(https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/faf.12425)

See also:

Report on Automated Data Collection Technologies (second Edition), March 2002, The Atlantic Coastal Cooperative Statistics Program (https://tinyurl.com/y2ez46zz).

Ames, Robert T. The efficacy of electronic monitoring systems: a case study on the applicability of video technology for longline fisheries management.2005. International Pacific Halibut Commission. Scientific Report No. 80. https://iphc.int/uploads/pdf/sr/IPHC-2005-SR080.pdf.

So I’ll end with a question. Why is it that, in spite of all of the obvious problems even prior to the Covid-19 crisis, there has been negligible progress implementing electronic monitoring in the majority of our domestic fisheries. For what is spent every year on federal and privately provided observers (the cost of which is increasingly being passed on to the fishermen and therefore to the consumers) why are we still years away from what is a “tech fix” that seems to be readily – if maybe not easily – achievable?