Wind Turbine Development and the future of fishing? Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet USA

Sept. 6, 2018 Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet USA

Let’s start with commercial fishing perspectives on wind farms in the North Sea:

Seventeen fishing vessels docked in the centre of Amsterdam, a city that built its wealth and prosperity on the herring fishery. Between 600 and 700 fishermen from Holland and Belgium arrived in the city for a peaceful but highly visible protest that was followed by dozens of journalists. The protest made primetime news slots on Dutch and Belgian TV, highlighting the problems the North Sea fishermen face. ‘European rules like the discard ban, plus the growing number of wind farms in the North sea, are a huge burden to the Dutch fishing industry,’ said Job Schot, chairman of the EMK action group that unites 125 vessels, making it clear why the fishing industry has brought its grievances to Amsterdam .‘If nothing changes, there will be no future for the next generation,’ he said, as a petition of demands for Dutch and European policymakers was delivered to Dutch MEP Annie Schreijer-Pierik of the Christian Democrat party. EMK is seeking for no more wind farms to be located on fishing grounds and spawning grounds, for more research to be conducted into he effects of wind farms on marine life, and for compensation for the indystry’s losses.

(From Fishermen take protest to Amsterdam, Fisker Forum, 03/06/2018, https://tinyurl.com/y7wh4ovw.)

“At the moment I’m having to steam three hours to catch fish,” he (Steve Barratt, commercial fisherman out of Ramsgate, England) says. “Two reasons I’m having to steam three hours: one, to try and avoid fish I have no quota for, and the other reason is the wind farm’s in the way.”

From a seaside bluff in Broadstairs, another harbor just up the road from Ramsgate, you can just make out the north coast of France. And much closer, a row of wind turbines — the same farm fisherman Barratt will head through later on his way to Dutch waters. That’s where I meet John Nichols, who helps run the local fishermen’s association. He says 10 years ago, fishermen here thought offshore wind was a pipe dream. By the time they got together to oppose it, it was too late. Nichols says New England’s fishermen shouldn’t waste time fighting wind farm developers.

Instead, he says, they should form fishermen’s associations to increase their bargaining power.”You can’t work against them, you’ve got to work with them,” he says. “But if you’re one fisherman going to a developer, he won’t have any time for you. But if you’re, in our case 40-plus boats, then they will listen to you. And I think that’s the most important thing: strong, it can be small, but strong associations.”

(From Why Some Fishermen Are Wary Of Offshore Wind Farms, Chris Bentley, 01/17/18, WBUR Boston, http://www.wbur.org/bostonomix/2018/01/17/fishermen-wind-farms-england)

Moving on to:

New Jersey under Gov. Phil Murphy is fully committed to offshore wind, working toward generating 3.5 gigawatts of its clean energy by 2030. The Board of Public Utilities has been ordered to prepare to seek bids on more than 1,000 megawatts of wind power, and a Danish company with a lease for an ocean wind farm has opened an office in Atlantic City. So when the governor asked early last month for another 180 days to comment on the next round of vast ocean wind leases — this time in the much used and fought over New York Bight between the city’s harbor, Long Island and South Jersey — his request was very credible. Our view: Murphy gets state, fishing industry more time for wind energy plan, Atlantic City Press, 06/01/18, https://tinyurl.com/ya29dho8.

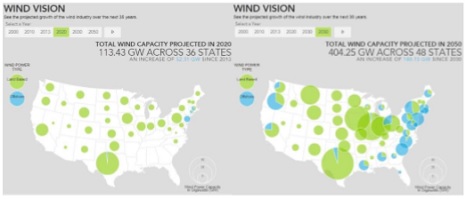

Notice that most of the growth in offshore wind energy – via wind turbines – is off the northeast states (that coincides with the presence of a wide continental shelf, a lot of suitably shallow water, and a high demand for electricity), America’s Future Has Wind In Its sails Sails, Magill, B., 2015, at http://www.climatecentral.org/news/america-future-wind-power-19020.

Last but not least:

The federal Bureau of Offshore Energy Management, which is in the U.S. Department of the Interior, was created in the aftermath of the greatest man-made catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (and the federal government’s catastrophic response to that spill and subsequent “clean up), is in the process of soliciting proposals for the development of wind power projects in several distinct “call areas” in the New York Bight.

“This announcement (Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 70 / Wednesday, April 11, 2018 / Notices, Pgs 15602 et seq.) also requests comments and information from interested and affected parties about site conditions, resources, and multiple uses in close proximity to, or within, the Call Areas that would be relevant to BOEM’s review of any nominations submitted and/or to BOEM’s possible subsequent decision to offer all or part of the Call Areas for commercial wind leasing.” (https://www.boem.gov/NY-Bight-Call-Area-Maps/)

Extending from the waters off Long Island on the north to Cape May at the southern tip of New Jersey, if these areas are fully developed then access to the New York Bight’s highly productive waters by fishing vessels from New Jersey and New York ports could be restricted to 4 narrow channels which are subject to a tremendous amount of maritime traffic 24/7. Not only would a tremendous amount of highly productive bottom be closed to commercial fishing, access to areas that remained open would be much more difficult and costly to reach. Rather than steaming directly to where they intended to fish, vessels would be forced to make detours around the wind “farms” that would add at best hours and at worst days to every fishing trip.

In spite of the fact that in the U.S. our experience with producing electricity with offshore wind turbines is virtually nonexistent, we are apparently well on the way to committing billions of dollars to the effort – and most of that effort is going to be in the waters off New England and the mid-Atlantic.

How much experience do we have with offshore wind turbines in the United States?

The Block Island Windfarm is made up of the only offshore wind turbines in operation off the United States today. It is 3.8 miles off Rhode Island’s Block Island and consists of 5 turbines, each having a 6 MW (Megawatt) capacity. The “windmills” are 600 feet high and can reportedly withstand a Category 3 storm. Their connection to the electrical grid is via a 21 mile cable buried in the sea bed that comes ashore in Narragansett, RI*.

But these wind turbines are hardly “state of the art.”

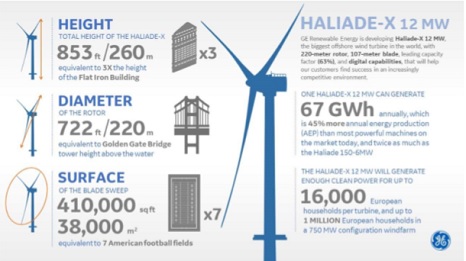

GE Renewable Energy has introduced the Haliade-X 12 MW, a 12 MW wind turbine that will be 853 feet tall with a rotor 220 meters in diameter generating “almost 45% more energy than (the) most powerful wind turbine on the market today.” (https://www.ge.com/renewableenergy/wind-energy/turbines/haliade-x-offshore-turbine)

Note the height of 853 feet and the blade sweep of 410,000 square feet. Though I couldn’t find velocity figures for blade tip velocities for the Haliade-X 12, the Siemens B75 turbine, the largest capacity wind turbine in use today, has a reported blade tip velocity of 180 miles per hour (https://tinyurl.com/y92oz69f).

(Agglomerations of wind turbines are usually referred to, at least by proponents, as either “wind farms” or “wind parks.” Is it just me or do other folks fail to see anything either farm- or park-like in a bunch – sometimes numbering in the hundreds – of huge structures each as tall as the Eifel Tower with blades sweeping almost 40,000 square meters with every revolution? How bucolic. How peaceful! How misleading!)

It would take 83 Haliade-X 12 MW wind turbines to generate New Jersey Governor Murphy’s initial 1,000 megawatts, and 291 turbines to reach his goal of 3.5 gigawatts of offshore generating capacity off New Jersey.

New Jersey’s coastline is about 130 miles long. If Governor Murphy’s 291 wind turbines are equally spaced from Sandy Hook to Cape May, they would be about half a mile apart.

At least at this point it seems that the domestic commercial fishing industry will be sharing – or trying to share – the oceans with thousands of huge wind turbines, and thousands of miles of sea floor transmission lines and the electromagnetic fields that that they create*.

But how cooperative is that sharing likely to be?

In 800 megawatt floating turbines proposed off California (in WorkBoat 03/22/2016, https://tinyurl.com/y9jcps2k) Kirk Moore writes “the company (Trident Winds, LLC) says it has been talking to Morro Bay commercial fishermen too, and drew its proposed area with an eye to avoiding conflicts. On its website, Trident says “there is no exclusion zone required on the wind farm perimeter, but the area will prohibit commercial fish trawling and netting.” The total amount of bottom from which fishing with nets will be excluded will amount to 68,000 acres (or 106 square miles). Prohibiting what are among the most efficient – and sustainable – forms of fishing in over 100 square miles of productive ocean bottom doesn’t seem to be a particularly effective way of “avoiding conflicts.”

A report commissioned by the National Wildlife Federation, Catching the Wind (https://tinyurl.com/yb8hehgw), estimates that 16,249 megawatts of energy could be produced by offshore wind turbines from Massachusetts to Virginia. Using the estimate from Trident Winds of 8 megawatts/square mile above, this would mean that commercial fishing would be prohibited over on the order of 2,000 square miles of ocean in the mid-Atlantic and Southern New England. This, of course, would be on top of other closures mandated for a variety of management, conservation and preservation purposes.

And this doesn’t take into consideration any additional commercial fishing closures required for transmission lines or other “off the farm/park” infrastructure.

Putting this into perspective, the coastline from the Massachusetts/New Hampshire border to the Virginia/North Carolina border is about 600 miles long. In this area there are on the order of 9,000 square miles of ocean from the coast to fifteen miles offshore. Good luck on closing up to 2,000 square miles of this (plus transmission infrastructure requirements) to nets without conflicts.

To a very large extent the future of the domestic commercial fishing industry is going to depend on how well it integrates with the offshore power industry, and that is going to take a great deal of coordination and cooperation. And that level of coordination and cooperation isn’t going to happen unless the political will is there to guarantee that it does. It appears as if the European experience in the North Sea will provide a template of what not to do. Will we be able to learn from that – and will the research be done that will allow the same level of precaution to be applied to offshore wind turbines as is applied to fishing?

Fishermen’s

A group of fishing organizations, businesses, and communities, led by the Fisheries Survival Fund (FSF), has moved forward with its lawsuit to halt the leasing of a planned wind farm off the coast of New York. The suit, filed against the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), is seeking summary judgment and requesting the court to invalidate the lease, which was awarded to the Norwegian firm Statoil to develop the New York Wind Energy Area (NY WEA).

BOEM’s process for awarding the lease failed to properly consider the planned wind farm’s impact on area fish populations and habitats, shoreside communities, safety, and navigation. This violates the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires an assessment of these impacts before issuing the lease, in conjunction with a full Environmental Impact Statement and an evaluation of alternative locations for any proposal. Ten commercial fishing industry organizations and three fishing communities are plaintiffs in a lawsuit (from Fishing Groups and Communities Move Forward with Suit Against NY Wind Farm, 9/19/17, at https://tinyurl.com/y6u9aps7).

Suing federal agency is exceedingly expensive, and having to bring a suit every time BOEM – or any other federal agency that threatens commercial fishing through its permitting process would be prohibitively expensive – and is obviously not the answer. Fortunately our federal fisheries are already being managed by six regional fishery management councils. It would be logical to give these Councils a strong role in the siting of development of offshore energy, transmission cables and other associated developments. Without that our fishing industry is going to be submerged by a tsunami of windmills, submerged data centers (see Microsoft deploys underwater data center off the coast of Scotland, 06/07/2018 at https://tinyurl.com/ydaujfn5, and associated hardware.

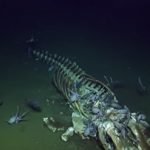

*In December I wrote EMF (Electromagnetic Field) Effects and the Precautionary Principle (https://tinyurl.com/yc5t7d7a). In it I addressed the paucity of research on the impacts EMFs generated by electrical currents on marine organisms and of the willingness of the environmental community to insist on the application of the precautionary principle to fisheries management while ignoring it as it applies to EMFs. Stated most simply, we don’t have much of a clue about their impacts – both acute and long-term – on the plants and animals that sustain our multibillion dollar fishing and tourism industries.