Search Results for: Nils Stolpe

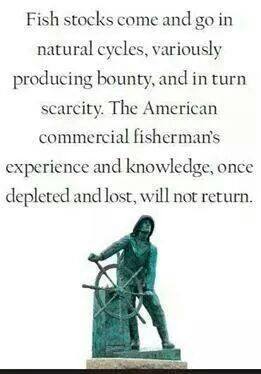

Nils Stolpe – Fishosophy – A New Blog and, Is this any way to manage a fishery?

“Deep-Sea Plunder and Ruin” reads the title of an op-ed column in the New York Times on October 2 (also in the International Herald Tribune on October 3). The column, by two researchers who focus on oceanic biological diversity, is aimed at pressuring the Fisheries Committee of the European Parliament to “phase out the use of deep-sea-bottom trawls and other destructive fishing gear in the Northeast Atlantic.”,,,and, Is this any way to manage a fishery? The status of river herring and shad has be an ongoing concern of anyone interested in the well-being of the fisheries in the Northeast U.S. From high abundance a few decades back these anadromous fish are presently at low levels. more here 18:59

“Deep-Sea Plunder and Ruin” reads the title of an op-ed column in the New York Times on October 2 (also in the International Herald Tribune on October 3). The column, by two researchers who focus on oceanic biological diversity, is aimed at pressuring the Fisheries Committee of the European Parliament to “phase out the use of deep-sea-bottom trawls and other destructive fishing gear in the Northeast Atlantic.”,,,and, Is this any way to manage a fishery? The status of river herring and shad has be an ongoing concern of anyone interested in the well-being of the fisheries in the Northeast U.S. From high abundance a few decades back these anadromous fish are presently at low levels. more here 18:59

Commercial fishing in the Northeast: a decade of change – Nils Stolpe, FIshNet USA

I had the honor of being asked to write an article to be included in the program for the 2013 New Bedford Working Waterfront Festival. While much of it has be covered in prior FishNets, I thought that some readers might be interested in it, so it is reproduced below. It is available as a pdf file from gardenstateseafood.org. Nils E. Stolpe – FishNet USA 14:44

I had the honor of being asked to write an article to be included in the program for the 2013 New Bedford Working Waterfront Festival. While much of it has be covered in prior FishNets, I thought that some readers might be interested in it, so it is reproduced below. It is available as a pdf file from gardenstateseafood.org. Nils E. Stolpe – FishNet USA 14:44

Seafood certification – who’s really on first? Nils Stolpe

![]() “Sustainability certification” has become a watchword of people in the so-called marine conservation community in recent years. However, their interest seems to transcend the determination of the actual sustainability of the methods employed to harvest particular species of finfish and shellfish and to use the certification process and the certifiers to advance either their own particular agendas or perhaps the agendas of those foundations that support them financially. continued here

“Sustainability certification” has become a watchword of people in the so-called marine conservation community in recent years. However, their interest seems to transcend the determination of the actual sustainability of the methods employed to harvest particular species of finfish and shellfish and to use the certification process and the certifiers to advance either their own particular agendas or perhaps the agendas of those foundations that support them financially. continued here

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is the largest international organization – headquartered in London – providing fish and seafood sustainability certification. It was started in 1996 as a joint effort of the World Wildlife Fund, a transnational ENGO, and Unilever a transnational provider of consumer goods.

David and Lucille Packard Foundation, Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Monterey Bay Aquarium, National Park Service, NOAA, Obama Victory Fund., Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis, Resources Legacy Foundation, Senator Lisa Murkowski, The Writings of Nils Stolpe, US Department of the Interior, Walmart, Walton Family Foundation, World Wildlife Fund

Nils Stolpe – Fisheries Management–More Than Meets The Eye

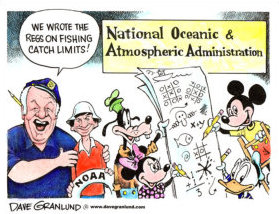

![]() Last year I wrote After 35 years of NOAA/NMFS fisheries management, how are they doing? How are we doing because of their efforts? (http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

Last year I wrote After 35 years of NOAA/NMFS fisheries management, how are they doing? How are we doing because of their efforts? (http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

Our collective fisheries were never as badly off as grandstanding ENGOs convinced the public and our lawmakers that they were. Regardless of that, they are unquestionably in great shape now. Are the fishermen – the only people who have paid a price for that recovery – going to profit from it? At this point there aren’t a lot of indications that they are going to. Ill-conceived amendments to the Magnuson Act, the ongoing foundation-funded campaign to marginalize fishermen and to hold them victims of inadequate science, and a management regime that is focused solely on the health of the fish stocks and is indifferent to the plight of the fishermen effectively prevent that. continued here

Nils Stolpe: A staggering loss to U.S. fishermen and U.S. seafood consumers. And while on the subject of press releases…. CLF and Earthjusice

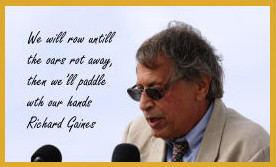

It was back in June of 2008 that I first became aware of Richard Gaines’ work in the Gloucester Times in a three part series exploring the interplay between fishermen, feds, ENGOs and the mega-foundations that funded them in a controversial move to close Stellwagen Bank to fishing (see http://tinyurl.com/n8m3voh for the first installment). A letter about the series I wrote to Times Editor Ray Lamont started “kudos to Richard Gaines for reporting what is going on behind the smoke and mirrors obscuring the struggle to maintain the historical fisheries that have thrived on Stellwagan Bank for generations. He couldn’t be more on-target when writing ‘Pew is associated with public information campaigns against fishing and fish consumption.’” continued@thewritingsofnilsstolpe

It was back in June of 2008 that I first became aware of Richard Gaines’ work in the Gloucester Times in a three part series exploring the interplay between fishermen, feds, ENGOs and the mega-foundations that funded them in a controversial move to close Stellwagen Bank to fishing (see http://tinyurl.com/n8m3voh for the first installment). A letter about the series I wrote to Times Editor Ray Lamont started “kudos to Richard Gaines for reporting what is going on behind the smoke and mirrors obscuring the struggle to maintain the historical fisheries that have thrived on Stellwagan Bank for generations. He couldn’t be more on-target when writing ‘Pew is associated with public information campaigns against fishing and fish consumption.’” continued@thewritingsofnilsstolpe

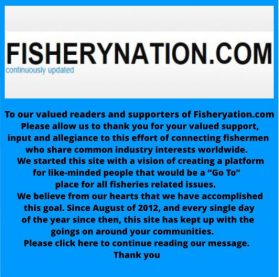

The Writings of Nils Stolpe

Nils Stolpe is our Honored Guest. Click on the fishnetUSA icon to open the window to his website.

It is our job to see that this dialogue is entered into based on solid data and sound science, not on spin and hype.

•There are many ongoing river herring and shad conservation efforts at various levels which are already coordinated by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (Commission) and NOAA Fisheries; • The Commission and states have recently increased their control of state landings;

• The pending catch caps for river herring and shad in the Atlantic mackerel and Atlantic herring fisheries will control fishing mortality of river herring and shad in Federal waters;

• NOAA Fisheries recently found that river herrings are not endangered or threatened and that coastwide abundances of river herrings appear stable or increasing; • Additional research into stock abundance is needed to establish biological reference points; and

• NOAA Fisheries has recently committed to expanded engagement in river herring conservation.” Yet even in spite of this – and, I’ll be so presumptuous as to add that the Council’s and its staff’s resources appear to be maxed out at this point so any additional tasks would be at the expense of existing efforts – the Council did agree to bring together an interagency working group on river herring and shad, the progress of which the Council will periodically review beginning with its June 2014 meeting.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Towards rationality in fisheries management/FishNet USA

–

Bearing in mind that each edition of The Economist has a print circulation of about 1.5 million, its website attracts about 8 million visitors each month, and that the people who read it are among the world’s most influential, consider the “take home” message that anyone with little or no knowledge of fisheries – maybe 99% of the readers – is being given; that stability of production in a fishery is an indication of overfishing, and even more importantly, that overfishing is unacceptable because it limits production.

–

Now we all know that sustainability is the managers’ goal in our fisheries. In fact, this goal is part of the legal underpinnings of each of the fisheries management plans in effect in – and sometimes beyond – the US Exclusive Economic Zone.

–

According to the legislation controlling fisheries management in US federal waters, the first National Standard for Fishery Conservation and Management is that “conservation and management measures shall prevent overfishing while achieving, on a continuing basis, the optimum yield from each fishery for the United States fishing industry.” This is fine up to a point. The optimum yield from a fishery is defined in the Act as “(A) the amount of fish which will provide the greatest overall benefit to the Nation, particularly with respect to food production and recreational opportunities, and taking into account the protection of marine ecosystems; (B) is prescribed as such on the basis of the maximum sustainable yield from the fishery, as reduced by any relevant economic, social, or ecological factor.” No problems so far, the law recognizes that the optimum harvest from a fishery is not necessarily the maximum sustainable harvest.But then we have “(C) in the case of an overfished fishery, provides for rebuilding to a level consistent with producing the maximum sustainable yield (MSY) in such fishery.”

–

Adding their interpretation to this, the people at NOAA/NMFS, with the enthusiastic support of the various and sundry anti-fishing activists who pull way too many of the strings in Washington, have added as an administrative guideline that “the most important limitation on the specification of OY (optimum yield) is that the choice of OY and the conservation and management measures proposed to achieve it must prevent overfishing.”

–

So while OY from each fishery, determined with consideration given to relevant economic, social, or ecological factors, seems to be the goal of federal fisheries management, that is just window dressing. The real requirement is for each and every fishery to be at MSY.

–

From an administrative perspective, a perspective that has far more to do with the influence that the aforementioned activists had and continue to have than on the real-world needs of commercial and recreational fishermen and the communities and businesses that they support, this probably makes a certain amount of sense. After all, who could possibly argue about every fishery faithfully producing at maximum levels year after year? As the people at The Economist, at the ENGOs whose bank accounts are bloated with mega-foundation cash, and in the offices of Members of Congress who don’t have – or who don’t value – working fishermen as constituents want to convince us all, overfishing is something akin to the eighth deadly sin.

–

But is it?

–

From a real world perspective, a perspective that is shared by an increasing number of people who are knowledgeable about the oceans and their fisheries and who value the traditions and the communities that have grown up around them as well as the economic activity that fisheries are capable of producing, this proscription against “overfishing” is an ongoing train wreck.

–

And at this point, because it’s The Law, nothing can be done about it.

–

A hypothetical situation:

–

Suppose there was an important fishery that was the basis of a large part of the coastal economy as well as the cultural cement that held coastal communities together. Then suppose that fishery started to decline. If you were a fishery manager and you were in charge, what would you do? Though not in what should be the real world, that’s a simple question with an even more simple answer in today’s world of federal fisheries management. Regardless of any other factors you would cut back on fishing effort.

–

Suppose that didn’t work, suppose that the fishery continued to decline. What would you do then? Because you have no other realistic options you’d cut back on fishing effort even more.

–

And suppose even that didn’t work. If there were still any fishermen fishing, you’d cut back their fishing effort yet again. And again and again and again until you had gotten rid of them all, in spite of whether the cutbacks had any noticeable effects of the fish or not.

–

As we saw above, this would all be based on a so-called fishery management “plan” that was created under the strict requirements of a surprisingly short and what has become an even more surprisingly short sighted bit of federal legislation and the administrative interpretation of that legislation. The Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA) – which was written initially with good intentions towards US fishermen and signed into law in 1976 – has been purposefully distorted by outside groups and individuals with no legitimate ties to or empathy with the businesses and people dependent on fishing but with huge budgets provided by mega-foundations which themselves are provided with a convenient government-supplied coordinating mechanism (See http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

–

Why is it a “so-called” management plan? Back a few more years than I’d like to acknowledge I spent some time in the graduate planning department at Rutgers University, concentrating on environmental planning. Not too surprisingly, one of the topics that came up repeatedly was rational planning; what it is and how to do it. Putting together a bunch of definitions and some foggy recollections, in creating a rational plan you 1) define a problem or a goal, 2) design alternative actions to solve the problem/achieve the goal, 3) evaluate each alternative action, 4) chose and implement the “best” alternative action, and 5) monitor/evaluate the outcome and adjust if necessary.

–

This seems pretty simple and straightforward. How does it apply to fisheries management plans? If the problem with the New England groundfish fishery is that there are people making a living based on harvesting groundfish and if the goal is to stop them from doing that, then the managers and the management plan are right on target. But I suspect that most involved individuals/organizations aren’t purposely planning to solve that problem/achieve that goal.

–

So why, after a seemingly endless series of less groundfish can only be fixed by less groundfish fishing iterations, are the groundfish fishermen – those who are still working – and the communities that depend on them just barely hanging on with fewer fish to catch following each cutback in fishing effort?

–

While this idea is going to be ridiculed by all of those anti-fishing activists whose careers are predicated on blaming just about every ocean ill on overfishing, perhaps it’s because overfishing isn’t the problem that they’ve built multimillion dollar empires on by convincing the world – and the U.S. Congress – that it is.

–

But for the moment let’s pretend that we don’t have a fisheries management system that has been torqued into something worse than ineffectuality by their lobbying clout. Let’s pretend that the people responsible for creating fisheries management plans in general and the groundfish plan – actually the multispecies plan – in particular were trying to do some rational planning. Where would they go from here?

–

What about competition between species?

–

Obviously, having lived with the effectiveness – or the lack thereof – of continuously cutting back on groundfish fishing, they’d look for an alternative or two (and no, opening parts of several previously closed areas of the EEZ while demanding full-time, industry paid observer on every vessel that fishes in them isn’t anything approaching a reasonable alternative). It’s hard to imagine that early on they wouldn’t consider the idea that other, competing species might be in part responsible for declining stocks. That’s the way the natural world has worked, is working and will continue to work.

1953 – Spiny dogfish biomass unknown – “Voracious almost beyond belief, the dogfish entirely deserves its bad reputation. Not only does it harry and drive off mackerel, herring, and even fish as large as cod and haddock, but it destroys vast numbers of them. Again and again fishermen have described packs of dogs dashing among schools of mackerel, and even attacking them within the seines, biting through the net, and releasing such of the catch as escapes them. At one time or another they prey on practically all species of Gulf of Maine fish smaller than themselves, and squid are also a regular article of diet whenever they are found.” (Fishes of the Gulf of Maine, Bigelow, H.B. and W.C. Schroeder)

About ten years ago fishermen started complaining about the impact that the huge numbers of spiny dogfish off our coast were having on other much more valuable fisheries. As a result I organized a workshop on spiny dogfish/fisheries interactions in September of 2008 (see A Plague of Dogfish at http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

–

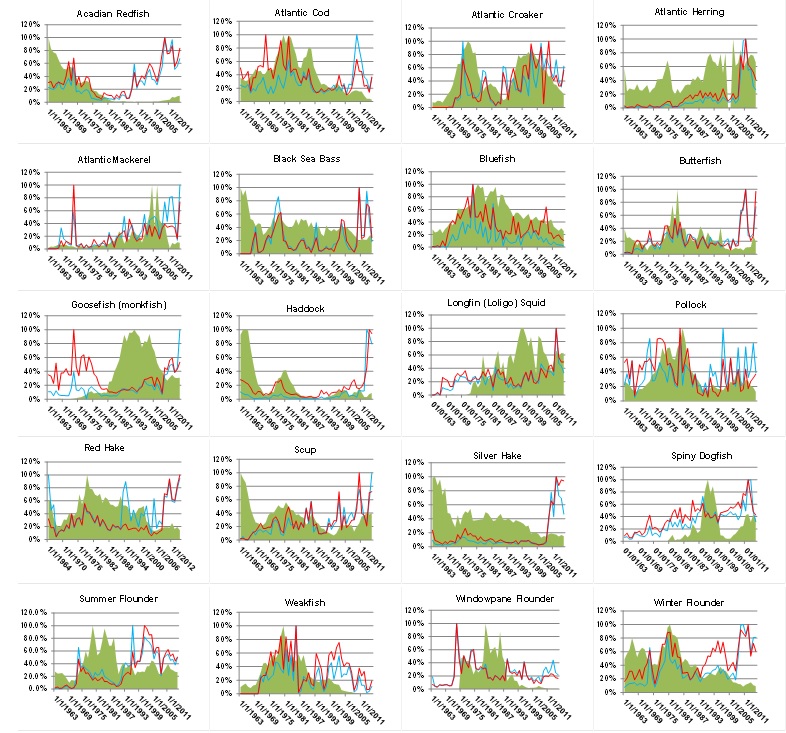

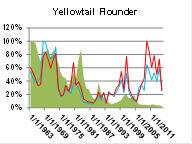

Among the most interesting data sets I have found are the reports of the bottom trawl surveys which have been carried out by Northeast Fisheries Science Center vessels every year for over half a century (to access the recent reports go to http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/

–

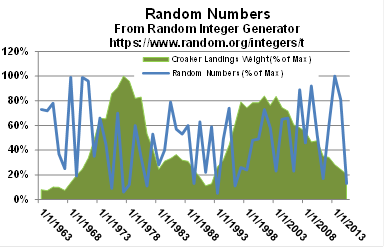

Looking for another way of addressing the spiny dogfish situation, I put together a spreadsheet of the percentage (by weight) of spiny dogfish and Atlantic cod caught in the Spring and Autumn bottom trawl surveys for the last ten years and graphed the results (because the annual Winter survey was discontinued half way through this time period, I omitted it).

I was surprised to see how well the high abundance levels of spiny dogfish coincided with the low abundance levels of Atlantic cod – the primary groundfish species – and vice versa. (Note that this relationship wasn’t apparent in prior years.)

It seems in-your-face obvious that in recent years there been something going on between spiny dogfish and Atlantic cod abundance (I looked at the trawl survey results for a number of other species relative to spiny dogfish and none of them exhibited such a dramatic apparent relationship).

–

Of course this could be an example of post hoc ergo propter hoc (basically correlation doesn’t equal causation). But then again, it could not as well.

1992 – Spiny dogfish biomass estimated at 735 thousand metric tons: “given the current high abundance of skates and dogfish, it may not be possible to increase gadoid (cod and haddock) and flounder abundance without `extracting’ some of the current standing stock.” (Murawski and Idoine, Multi species size composition: A conservative property of exploited fishery systems in Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, Volume 14: 79-85)

James Sulikowski at the University of New England in Biddeford, Maine has been intensively involved in shark and ray research for twenty years. He is currently focusing on spiny dogfish and along with population and distribution work has begun to look at prey and predation. According to Dr. Sulikowski “preliminary analysis of stomach content data suggest a high degree of dietary overlap between dogfish and Atlantic cod as Atlantic herring, Cluepea harengus, was found to be the primary prey item of both species. In addition, preliminary stable isotope data suggests evidence of niche overlap between cod and dogfish, although the extent of overlap may change seasonally. Collectively, the stomach content and stable isotope data suggests dogfish and cod are in competition for resources within this ecosystem.”

–

How does this apply to the current Northeast Multispecies (groundfish) Fisheries Management Plan?

–

In fact, it doesn’t apply at all. The multispecies plan is based on the assumption that fishing is the only thing influencing the groundfish stocks – including Atlantic cod. Considering that fishing is the only thing that federal legislation permits the New England Fishery Management Council to manage, its members have become quite adept at managing it. The fact that an extensive and still ongoing series of fishing cutbacks hasn’t stopped the decline of the primary groundfish species – led by Atlantic cod – seems to be irrelevant to them doing that.

1994 – Spiny dogfish biomass estimated as 514 thousand metric tons: “…preliminary calculations indicated that the biomass of commercially important species consumed by spiny dogfish was comparable to the amount harvested by man. Accordingly, the impact of spiny dogfish consumption on other species should be considered in establishing harvesting policies for this species.” (18th Stock Assessment Workshop, Northeast Fisheries Science Center).

The graph below shows the spiny dogfish total biomass estimates from the Northeastern Fisheries Science Center’s spring bottom trawl surveys. The highest estimated biomass, 1.131 million metric tons (or about 2.5 billion pounds), was in 2012 (from data in in Table 7 of Update on the Status of Spiny Dogfish in 2012 and Initial Evaluation of Harvest at the Fmsy Proxy by Rago and Southesby and MAFMC staff and identified as not representing “any final agency determination or policy”). For reference, the total allowed catch (TAC) of spiny dogfish will be under 20,000 metric tons (the solid red line) a year for the next three years.

2008 – Spiny dogfish biomass estimated at 657 thousand metric tons: “All told, 87% of the stomach contentsfrom these particular Gulf of Maine caught dogfish (401 adult dogfish collected by University of New England researcher James Sulikowski and his students) consisted of bony fish – with cod, herring, and sand lance being the top three species.” (J. Plante, Dogfish in the Gulf of Maine eat cod, herring, Commercial Fisheries News, May 2008).

_______________________________________________

The two graphs below – from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s web page Status of Fishery Resource off the Northeastern US – Atlantic cod (http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/

It has been reported that spiny dogfish consume 1.5% of their weight per day. That translates to them eating about 17000 metric tons of anything slower/smaller/less voracious than they are every day.

2009 – Spiny dogfish biomass estimated at 557 thousand metric tons: “our reason for ontacting you is to draw your attention to a severe and growing problem that we are all facing because of the supposed constraints imposed on the federal fisheries management system by the most recent amendments to the Magnuson Act. Because of the supposed necessity of having all stocks being managed at OY/MSY, all of our fisheries are and have been suffering from a plague of spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias).” (Fishermen Organized for Rational Dogfish Management letter to NOAA head Jane Lubchenco).

Since 1950 the annual Atlantic cod landings in all US ports exceeded 50,000 metric tons only in 1980, ‘82 and ‘83. In 2011 they were 7,900 mt.

–

If there was one rational step that could be taken to try to return the Atlantic cod stocks off our Northeastern coast to former levels, it’s hard to imagine anything with more of a likelihood of success than significantly cutting back the population of spiny dogfish. But this isn’t possible because if the spiny dogfish stock is not at a level that could produce the maximum sustainable yield it would be overfished – and thanks to the successful lobbying of the anti-fishing claque managed fish stocks can’t be overfished.

–

In the face of all of this it’s kind of hard to think that the federal fisheries management system has as a goal anything but the elimination of New England’s codfish fishermen. Otherwise, how could an alternative to further futile decreases in fishing for cod not be an increase in fishing for spiny dogfish? That would seem to be a rational action, wouldn’t it (and rest assured that spiny dogfish impact many more species than Atlantic cod).

But it’s not, and with the MSFCMA written and interpreted the way it is it can’t be.

–

But the spiny dogfish plague isn’t the only fly in the “blame it all on overfishing” ointment. There’s an explosion in the population of seals in New England coastal waters as well. With the ability – or more accurately, with the need – to consume 6% of their body weight per day, the almost 16,000 gray seals off Cape Cod are consuming far more fish than Cape Cod’s recreational and commercial fishermen could ever hope to catch. If they aren’t competing directly with the fishermen for cod and striped bass and flounder they are competing indirectly by eating the prey species that the fishermen’s targeted species eat. For a succinct and fairly balanced examination of the developing Cape Cod seal crisis see Thriving in Cape Cod’s Waters, Gray Seals Draw Fans and Foes by Bess Bidgood in the NY Times on August 17th. And there are burgeoning populations of other marine mammals as well as cormorants, birds that are protected by the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. They are all highly efficient predators on smaller fish.

–

The Act will be reauthorized this year. In the reauthorization, unless the managers are once again given the ability to use their judgment we won’t be able to most effectively manage our federal fisheries to maximize the benefit we can derive from them. The Magnuson management process was designed to benefit from the knowledge that people in the fishing industry and marine scientists have gained through uncounted years of on-the-water experience in dealing with an environment that is as strange to the rest of us as outer space and a lot more complex. The benefits of that knowledge have been lost to the process because of legislated changes by people who and organizations that are sorely lacking in that hands-on experience and think that there is one answer to every fishery-related problem – to cut back on fishing. Without that changing, without discretion being returned to the managers, our fisheries will increasingly follow the trajectory that the New England groundfish fishery is on. None of us – except perhaps for the ENGOs and the foundations that support them – either want or can afford that. Magnuson must be amended. Flexibility, with adequate safeguards, to deal with situations like the current dogfish plague must be restored to the management process. Rationality demands it.

————————————————————————————————

Seafood certification – who’s really on first?

“Sustainability certification” has become a watchword of people in the so-called marine conservation community in recent years. However, their interest seems to transcend the determination of the actual sustainability of the methods employed to harvest particular species of finfish and shellfish and to use the certification process and the certifiers to advance either their own particular agendas or perhaps the agendas of those foundations that support them financially.

It doesn’t take an awful lot of sophisticated insight to recognize that a “sustainable” fishery is one that has been in operation in the past, is in operation presently, and will be in operation in the future. That’s what sustainability is all about – for lobsters, for fluke, for surfclams, for guavas, for hemp, for alpacas, in fact for anything that can be grown and/or harvested.

(Of course “marine conservationists” would have us believe that a fishery that has a noticeable impact on the marine environment isn’t really sustainable. Imagine, if you can, a farm that has no environmental impact; in essence producing crops without interfering with the natural flora and fauna that “belong” there. That would get beef, cotton, soybeans, corn, mohair and what have you off the tables or out of the closets of perhaps 6 billion of the people who we share the world with, but if you are a committed marine conservationist, so what? The marine conservation community, and the foundations that support it, has been frighteningly successful in convincing people that “sustainable fishing” is actually “no impact fishing,” but as we learned quite a few years ago, even hook and line fishermen catching one fish at a time can have a far from negligible environmental impact.)

Several recent events have increased the focus on sustainability and its use – or misuse – in attempts at influencing the buying habits of the seafood consumers.

In the first of these, Walmart (the world’s largest retailer) now requires its fresh and frozen fish/seafood suppliers to “become third-party certified as sustainable using Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) or equivalent standards. By June 2012, all uncertified fisheries and aquaculture suppliers must be actively working toward certification.”

In the second, the National Park Service in the US Department of the Interior announced that all of its culinary operations “where seafood options are offered, provide only those that are ‘Best Choices’ or ‘Good Alternatives’ on the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch list, certified sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council, or identified by an equivalent program that has been approved by the NPS.” Senator Lisa Murkowski questioned Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis about this “recommendation” (the term he used) at an Energy and Natural Resources Committee. She asked whether NOAA (the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration) was involved in formulating this recommendation. He responded that he didn’t know. Senator Murkowski responded “NOAA is the agency that makes the determination in terms of what’s sustainable (as far as fisheries are concerned) within this country”

When considered in a vacuum these are both interesting comments on the importance that is being put on “sustainability” by fish/seafood providers, and is indicative of a positive trend by consumers who are increasingly demanding that the products they buy are produced in an environmentally acceptable manner.

And the fact that a federal agency, the National Park Service, would demand – or as Director Jarvis waffled – would recommend that its vendors provide only seafood certified sustainable by two non-governmental organizations while ignoring the de facto certification that is implicit in federally managed fisheries is not likely to surprise anyone with any familiarity with the morass that the federal bureaucracy has become. However, neither Walmart nor the US Department of the Interior exists or operates in a vacuum, and it seems as if there is a bit more at work here than is obvious.

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is the largest international organization – headquartered in London – providing fish and seafood sustainability certification. It was started in 1996 as a joint effort of the World Wildlife Fund, a transnational ENGO, and Unilever a transnational provider of consumer goods.

The chart below lists recent grants to the MSC by the Walton Family Foundation and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation in recent years.

Grants to MSC from Walton Family Foundation

2007 $1,640,000

2007 $820,000

2008 $1,675,000

2009 $1,700,000

2009 $1,700,000

2010 $4,622,500

2011 $3,122,500

2012 $1,250,000

Total $16,530,000

http://www.

Grants to MSC from David and Lucille Packard Foundation

2005 $1,750,000

2006 $1,500,000

2006 $100,000

2006 $87,900

2007 $1,500,000

2008 $1,506,000

2008 $250,000

2009 $4,050,000

2010 $125,000

2011 $1,900,000

2012 $250,000

2012 $550,000

2013 $250,000

Total $13,818,900

http://www.packard.org/grants/

The Monterey Bay Aquarium was established with an initial grant of $55 million from David and Lucille Packard. Their daughter Julie is Vice Chairman of the Packard Foundation. She is also Executive Director and Vice Chair of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Board of Trustees.

The MSC also lists the Resources Legacy Foundation as one of its supporters. The Resources Legacy Foundation has received $99 million from the Packard Foundation. One of its programs is the Sustainable Fisheries Fund, which along with its other activities provides funding ”reducing the financial hurdles confronting fishing interests that wish to adopt sustainable practices and potentially benefit from certification under MSC standards.”

According to CampaignMoney.com Ms. Packard donated $75,000 to the 2012 Obama Victory Fund.

In both of these initiatives NOAA/NMFS, the organization that provides virtually all of the data and other information that sustainability determinations are based on, that is required by federal law to stop unsustainable fishing in federal waters, and that performs its own sustainability analyses on those fisheries, has been completely left out of the picture.

All things being equal, this could just be passed off as business – and government ineptitude – as usual. However, when tens of millions of dollars in donations by mega-foundations with “marine conservation” agendas that are looked at skeptically by so many in the fishing industry are thrown into the mix, should this be considered as just more business as usual or does it warrant a much closer look?

———————————————————————————————-

Fisheries Management–More Than Meets The Eye

Last year I wrote After 35 years of NOAA/NMFS fisheries management, how are they doing? How are we doing because of their efforts? (http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

Our collective fisheries were never as badly off as grandstanding ENGOs convinced the public and our lawmakers that they were. Regardless of that, they are unquestionably in great shape now. Are the fishermen – the only people who have paid a price for that recovery – going to profit from it? At this point there aren’t a lot of indications that they are going to. Ill-conceived amendments to the Magnuson Act, the ongoing foundation-funded campaign to marginalize fishermen and to hold them victims of inadequate science, and a management regime that is focused solely on the health of the fish stocks and is indifferent to the plight of the fishermen effectively prevent that.

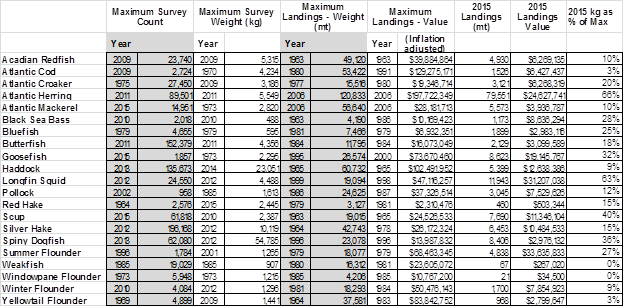

That having been a year ago, and statistics measuring the performance of our commercial fisheries for 2011 being available (http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/

Nationally, the total adjusted (to 2010 dollars) value of landings continued a gradual upswing that’s gone on intermittently since 2002/03. The post Magnuson (1976) low point in 2002 was under $4 billion, and by 2011 it had risen to over $5 billion, an increase of 35%. The adjusted value of the 2011 catch, $5.176 billion, was 76% of the highest total catch (in 1979) of $6.83 billion and 22% above the average landings (from 1950 to 2011) of $4.25 billion.

All in all, the big picture is mostly positive. Unfortunately, the big picture is made up of a lot of smaller pictures, and some of them aren’t so good.

In the following chart I separated the value of the total landings in Alaska and the separate values of landings in American lobster, sea scallops and Southern shrimp (all species combined) from all other species.

For total value of landings in 2011 Alaska is at about 70% of where it was at its post Magnuson high ($1.84 billion vs $2.58 billion). Atlantic sea scallops were at their all-time record value ($485 million) and American lobster were at 89% of their all-time high ($405 million vs $456 million in 2005). Unfortunately the 2011 (Southern) shrimp landings were valued at only 34% of what they were at their highest ($472 million vs $1.333 billion in 1979).

In 1950 the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries reported landings of 223 distinct species or species groups (i.e. Shrimp, Dendrobranchiata ). In 2011 the National Marine Fisheries Service reported landings of 460 species or species groups.

The 20 most valuable fisheries in 1950 and in 2011 and the percentage of their value to the total value of landings for that year are listed below:

|

1950 |

2011 |

|||

| Shrimp |

17% |

Sea Scallop |

14% |

|

| Yellowfin Tuna |

11% |

Shrimp (white & brown) |

11% |

|

| Eastern Oyster |

11% |

American Lobster |

10% |

|

| Skipjack Tuna |

7% |

Walleye Pollock (AK) |

9% |

|

| Pacific Sardine |

5% |

Sockeye Salmon (AK) |

7% |

|

| Haddock |

5% |

Pacific Halibut (AK) |

5% |

|

| Menhaden |

5% |

Pacific Cod (AK) |

5% |

|

| Sockeye Salmon (AK) |

4% |

Dungeness Crab (AK) |

5% |

|

| Sea Scallop |

4% |

Sablefish (AK) |

5% |

|

| Acadian Redfish |

4% |

Blue Crab |

4% |

|

| American Lobster |

4% |

Pink Salmon (AK) |

4% |

|

| Pacific Halibut (AK) |

3% |

Menhaden |

4% |

|

| Chinook Salmon (AK) |

3% |

Snow Crab (AK) |

3% |

|

| Quahog Clam |

3% |

King Crab (AK) |

3% |

|

| Coho Salmon (AK) |

3% |

Eastern Oyster |

2% |

|

| Pink Salmon (AK) |

3% |

Chum Salmon (AK) |

2% |

|

| Chum Salmon (AK) |

3% |

Pacific Geoduck Clam |

2% |

|

| Blue Crab |

2% |

California Market Squid |

2% |

|

| Striped Mullet |

2% |

Bigeye Tuna |

1% |

|

| Atlantic Cod |

1% |

Pacific Hake (AK) |

1% |

|

In the Mid-Atlantic in 2011 the total value of landings, $220 million, were 79% of the highest landings value reported ($279 million in 1979). However, sea scallops made up more than half of the total landings value (56%, $143 million v. $114 million). While the overall picture looks positive, the value of the landings in the Mid-Atlantic minus the sea scallop production have been in a steady decline since the late 90s and are at the lowest point ever.

In New England the situation is comparable, but both American lobster and sea scallop production are responsible for the overall “healthy” appearance. There was a slight upswing in the value of the other fisheries in recent years but it appears that with the planned – and in part implemented – reductions in the groundfish TAC, it seems as if this slight upswing won’t carry over.

Conservation and management measures shall, consistent with the conservation requirements of this Act (including the prevention of overfishing and rebuilding of overfished stocks), take into account the importance of fishery resources to fishing communities in order to (A) provide for the sustained participation of such communities, and (B) to the extent practicable, minimize adverse economic impacts on such communities. National Standard #8, Magnuson-Steven Fisheries Conservation and Management Act (As amended through October 11, 1996).

A looming problem in both the Mid-Atlantic and New England is a pending cutback in the sea scallop quota for the next fishing year that at this point is expected to approach 40%. While the effects of a cut of this magnitude will obviously be significant to the scallop fleet, there will be not so obvious but potentially devastating effects on the other fisheries and on fishing communities as well.

A complex of ancillary businesses is required to operate a commercial fishing dock. These include vessel/equipment maintenance and repair facilities, ice plants, chandleries and shippers/truckers. Obviously it requires a certain level of business – a minimum amount of revenue coming “across the dock” – for them to stay open. In the Mid-Atlantic a 40% cut in scallop revenues will be more than a 20% cut in commercial fishing revenues in a single year. In New England it will be somewhat less than that, but it will be combined with whatever additional cuts result from the proposed groundfish cuts.

I’m not that familiar with all of the fishing ports in the Mid-Atlantic and New England but have a fairly good understanding of those in New Jersey, and in New Jersey there isn’t one commercial port that lands fish from the ocean-going fleet that is mostly – or even largely – focused on scallops. They all handle a mix of fish and shellfish. A large part of their longevity is due to the fact that they have maintained a reasonable amount of flexibility thanks to their diverse fleets. But a drastic cutback in scallop revenues, particularly if it is coupled with the continuing decline in the revenues from other fisheries, will threaten that longevity.

The proposed scallop cutback has been presented as a temporary measure, and the Fisheries Survival Fund – representing the majority of limited access scallop fishermen in New England and the Mid-Atlantic and other industry groups are working to ameliorate the proposed cuts, but when it comes to businesses that are waterfront dependent a two year temporary reduction could easily become permanent before the cutbacks are restored. Except for the lull over the past several years there have been intense development pressures at the Jersey Shore and on most of the waterfront areas from Cape Hatteras North. It’s just about assured that they will be back to their customary levels very shortly.

Originally the Magnuson Act placed much more emphasis on business- and community-supportive aspects of federal fisheries management. Those aspects have been eroded by the lobbying activities of the handful of ENGOs that have come to dominate the world of fisheries/oceans activism. They, and for the most part NOAA/NMFS as well, address fish issues on a case by case, species by species basis. More importantly, the people at NOAA/NMFS tend to shy away from cumulative economic impacts when they have analyses done, and cumulative impacts are what most of the commercial fishermen, the people who depend on them and the businesses they support have to deal with – and in New England and the Mid-Atlantic (at least, and this isn’t to slight the industry elsewhere, because I doubt that it’s different in many other ports) in spite of increasing total landings value, it could be getting a lot worse really soon.

———————————————————————————————————————–

A staggering loss to U.S. fishermen and U.S. seafood consumers.

Nils E.Stolpe FishNet USA/June 26, 2013

It was back in June of 2008 that I first became aware of Richard Gaines’ work in the Gloucester Times in a three part series exploring the interplay between fishermen, feds, ENGOs and the mega-foundations that funded them in a controversial move to close Stellwagen Bank to fishing (see http://tinyurl.com/n8m3voh for the first installment). A letter about the series I wrote to Times Editor Ray Lamont started “kudos to Richard Gaines for reporting what is going on behind the smoke and mirrors obscuring the struggle to maintain the historical fisheries that have thrived on Stellwagan Bank for generations. He couldn’t be more on-target when writing ‘Pew is associated with public information campaigns against fishing and fish consumption.’”

This started a friendship between Richard and me that, I was amazed to discover, had lasted for less than five years. I know it enriched my life. I can only hope it enriched my writing as well.

Returning from a business trip on Sunday, June 9, Nancy Gaines found her husband Richard dead of an apparent heart attack at their home just outside of Gloucester.

Richard was a journalist’s journalist. Unlike the average “reporter” covering fisheries/ocean issues today, he gave press releases – and the contacts they provide – the minimal initial credence that they generally deserve. He was always looking for the story behind the press release and with a combination of integrity, skill and tenacity he usually found it. In five years he developed a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of what has become a cumbersomely complex federal fisheries management process – and of the political machinations behind it. Whether it was about the multi-billion dollar foundations behind the environmental activist organizations that have become so adept at making life miserable for fishermen, or a federal fisheries enforcement establishment that was allowed to enrich itself with tens of millions of dollars coerced from the fishing industry, Richard was covering it, covering it thoroughly and covering it well.

It’s going to be harder on all of us because he’s no longer there to do it.

Richard was memorialized fittingly by Ray Lamont in Community, industry mourn loss of a champion at http://preview.tinyurl.com/

And while on the subject of press releases….

“The Attorney General is wrong on the law and she is wrong on the facts,” said Peter Shelley, senior counsel with CLF, who has been actively engaged in fisheries management for more than 20 years. “Political interference like this action by Attorney General Coakley has been a leading cause of the destruction of these fisheries over the past twenty years, harassing fishery managers to ignore the best science available….We need responsible management which includes habitat protection and a suspension of directed commercial and recreational fishing for cod. We also need some serious leadership from our elected officials. Going to court or getting up on a political soapbox will not magically create more fish.” (from a Conservation Law Foundation press release on May 31.”

It’s kind of hard to believe that just about immediately after this press release went out the Conservation Law Foundation – along with the Pew spawned Earthjustice (recipient of some $20 million from the Pew Charitable Trusts) – filed suit in federal court to prevent NOAA from cutting the groundfish fishermen the tiniest bit of slack, perhaps allowing more of them to survive a largely management manufactured slump. It seems that in the release Mr. Shelley must have meant “other people going to court or getting up on a political soapbox will not magically create more fish. However if it’s me or my foundation funded buds going to court, watch out ‘cause those fish will shortly be on the way.”

I usually stay away from New England issues because my colleagues up there are more than capable – in spite of the gross inequities resulting from the mega-foundation mega-buck funding of organizations like the Conservation Law Foundation and Earthjustice – of representing their own interests. However I couldn’t sit back and not comment on the CLF position voiced by Peter Shelley in an article, Conservation group sues NOAA to block openings, byRichard Gaines on June 6.

Explaining how the CLF/Earthjustice position wasn’t hypocritical, Mr. Shelley explained “the distinction for me is that I have seen time and time again when politicians — in this case the attorney general — hasn’t participated in the (fisheries management) process, and then comes in to try to influence the process in litigation. They’re not taking a legal position, there’s not much there except politics.”(http://preview.

To suggest that this is a more than slightly puzzling statement for an attorney to make would be an understatement. Mr. Shelley must believe – or must want other people to believe – that Attorney General Coakley was acting on her own when filing the suit. Apparently he believes – or wants us to believe – that because she has never personally participated in the fishery management process her suit has no merit. He is and has been, it would seem, in attendance at many meetings in New England at which fish are discussed and it appears as if in his view this makes his suit de facto righteous and hers nothing more than political posturing.

Massachusetts Attorney General hasn’t participated in fisheries management?

Let’s examine his contention that the Massachusetts Attorney General hasn’t participated in the (fisheries management) process in a little more depth. First off, I doubt very much that Attorney General Coakley brought the suit on her own behalf. In fact, I’d bet dollars to donuts that she brought it on behalf of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Even Mr. Shelley must know that the Commonwealth, via a succession of capable and effective representatives, has for at least the last forty or so years participated heavily in federal fisheries management via the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act. Either Paul Diodati, Director of the Commonwealth’s Division of Marine Fisheries, or David Pierce, the Deputy Director, are at every meeting of the New England Fishery Management Council and Dr. Pierce is a member of that Council’s Groundfish Committee (as well as its Herring, Sea Scallop and ad hoc Sturgeon Committees and the Mid-Atlantic council’s Dogfish and Herring Committees). Mr. Diodati is also the Chairman of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission and the Co-Director of the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Institute. They aren’t on these bodies on their own behalf either. They are there representing the Commonwealth as well. And before they were there, their predecessors were, and they were just as deeply involved.

This commitment to and participation in the fisheries management process by the various representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts began long before Mr. Shelley, the CLF and the Pew Trusts discovered each other. The Commonwealth, as represented in the current suit by the Attorney General whose participation Mr. Shelley seems so intent in marginalizing, established its bona fides in fisheries management at least a century ago (and will hopefully remain involved far beyond the point when Mr. Shelley, the CLF and Pew move on to “greener” pastures).

In fact the groundfish management measures that Mr.Shelley’s justifiable (in his estimation) suit is aimed at were a work product of the New England Fisheries Management Council, an institution which was established by the Magnuson Act in 1976 that has been in continuous operation – with overlapping changes in membership and administration – since then. And in spite of Mr. Shelley’s so apparent disagreement with this fact, the Council is mandated by the Act to manage for the benefit of the fish, the fishermen and the fishing communities. The Council members voted by an over 75% majority (13 to 3) to support the measures that Mr. Shelley et al are now going to court – of course in a non-political fashion – to prevent. As opposed to Mr. Shelley’s “more than twenty years” trumpeted in the CLF press release,how many hundreds of years of collective fisheries science and management experience do the Council members and staff possess? How many collective years of management experience do the Council members whose votes Mr. Shelley and his pals are going to court to nullify have.

Evidently it isn’t fisheries management experience that Mr. Shelley finds so valuable. It’s whose management experience that matters.

These are the people, the agencies, the institutions, the experience and the actions behind the Commonwealth’s lawsuit – the one that Mr. Shelley wants us to believe is based on nothing more than “political posturing.”

And what of the constituencies being represented? Attorney General Coakley’s constituency is made up in large part of Massachusetts fishermen, all of those people, families and businesses that depend on them, all of the Commonwealth’s consumers who, apparently unlike Mr. Shelley et al, realize that a seafood dinner should involve something more satisfying and wholesome than a several-times-frozen lump of imported shrimp, tilapia or swai, and all of them, and us, who seriously appreciate fishing traditions going back to colonial times.

On the other hand, from what I’ve been able to discover (see http://www.fishtruth.net), Mr. Shelley’s, CLF’s and Earthjustice’s “constituents” are a handful of mega-foundations and well-to-do-donors, and I’d imagine a lot of internet “click here if you don’t like fishermen or fishing” residents of anywhere (but I’ll again bet those same dollars to those same donuts that very few of them are in coastal Massachusetts).

So few groundfish?

Then Mr.Shelley brings up what he wants us to consider the “fact” that there are so few groundfish available to the fishermen that they are no longer filling their annual quotas. To the uninformed (those “click here” constituents, for example) this probably seems a compelling argument for shutting down the fisheries, Mr. Shelley’s often stated goal. It must make sense to many people who are unfamiliar with our modern fisheries “management” regime as it has been distorted by lobbying by environmental activist organizations like CLF. In fact, however, there are other and much more believable causes of uncaught quota than not enough fish.

The first of these would be the existence of so-called “choke” species. Much more valuable fisheries can be shut down because of unavoidable bycatch of other species with much lower quotas. Take the situation in which two species – the targeted species and the “choke” species – are inextricably mixed during part of the fishing year. Fishermen, tending to be rational even when dealing with an irrational system such as the one that Mr. Shelley and his cronies have built, will avoid the target species in spite of its abundance because they know full well that when the catch limit for the “choke” species is reached both fisheries will be shut down. In essence they are leaving the uncaught quota “in the bank” for later harvest. Needless to say, that later harvest isn’t guaranteed and it’s easy to imagine that in many instances it remains uncaught.

Then there are the meager trip limits for some stocks. Catch shares or not, in instances it just isn’t worth it for some fishermen to run their boats offshore for a few hundreds of pounds – or less – of fish. They’ll remain tied to the dock or will target other species with quotas that will allow them more income.

And we can’t forget low prices at the dock. Fish markets have adjusted to the recent vast swings in supply of some of the traditional species (a testament to the lack of effectiveness of our fisheries management system) by switching to alternative products. With the most productive fishing grounds in the world in our EEZ it’s hard to imagine that tilapia is the most heavily consumed finfish in the U.S., but it is. Compensating for these often low prices is a large part of the reason for the development of alternative markets for our domestic fisheries, but it’s somewhere between extremely difficult and impossible to move large quantities of fish in small lots.

Then there’s the impact of changing environmental conditions on the traditional availability of species, Said most simply, fish aren’t necessarily where they have been found by fishermen for generations. Though Mr. Shelley apparently want you to think that means they’re not there at all, that’s not necessarily so. Fish stocks are dependent on water temperatures, as are the critters they feed on, and water temperatures have been changing significantly in recent years. Some areas that used to reliably produce a particular species of fish at a particular time of the year no longer do so. With the meager quotas and the continually increasing costs of running a boat a fisherman isn’t as likely to search for where the water temperature changes have driven the fish. Economics won’t allow it.

Additionally, fish surveys are operated as if our U.S. coastal waters exist in a steady state; that conditions today are as they were when the survey was started. The same spots are sampled at the same time every year, and when a particular species is no longer taken in the sample or is taken in reduced numbers, the automatic assumption is that fishing is the cause of “the problem” and that reducing or curtailing (ala Mr. Shelley) fishing is the solution. Compounding the real problem, the reduced availability of research funds, the probability of extending the scope of the surveys is pretty low.

In a follow-up article on June 10, Shelley elaborated that the suit filed by Attorney General Coakley was “political ‘soapbox’ posturing” while“our suits are not political… they’re strictly based on the facts, and we do it as a last resort”(http://preview.tinyurl.com/

Attorney General Coakley, Governor Patrick et al, please keep on keeping on. Effective fisheries management should involve much more than happy fish and happy ENGOs. When Congress passed the Magnuson Act in 1976 the Members realized this and it’s about time that the pendulum gets pushed back in the direction that it was intended to swing in. Fish count, but so do fishermen, fishing communities and seafood consumers. If the U.S. fishing industry is to survive, the initial balance that was amended out of the Act by intensive lobbying by foundation funded activists claiming to represent the public must be restored.

For more information on Shelley’s/the Conservation Law Foundation/Earthjustice lawsuit see Conservation Law Foundation & Earthjustice Make Unfounded Claims in Lawsuit Filing at http://preview.tinyurl.com/

…………………………………..

For those of you who were interested in the FishNet piece (available at http://www.fishnet-usa.com/

———————————————————————————————————————-

FishNet – USA/June 24, 2013 Nils E. Stolpe

On August 13, 1997 Josh Reichert, then Director of the Pew Trusts Environment Program and now Executive Vice President of the Trusts, in an op-ed column in the Philadelphia Inquirer titled Swordfish technique depletes the swordfish population wrote “the root problem is not only the size of the (swordfish) quota, the length of the season, or the number of vessels involved. It is how the fish are caught…. Use of longlines must be barred…. the fishery should be open to all – provided that swordfish are caught with hand gear, including harpoons and rod and reel. No swordfish should be taken until it has a chance to breed at least once, meaning that the minimum allowable catch size should be no less than 100 pounds. Such measures…. would put the Atlantic swordfish population back on the road to recovery.

” http://articles.philly.com/

In what has become typical Pew style, Mr. Reichert’s article was just a small piece of a frightfully well-funded campaign to “save the swordfish” from the depredations of the U.S. pelagic longline fleet. Involving scientists who had been willing riders on the Pew funding gravy train, enlisting restaurateurs into the campaign who hadn’t the foggiest idea what swordfishing or pelagic longlining was all about, and using the formidable Pew media machine which had earned its legitimacy with tens of millions of dollars in grants to journalism schools and broadcast outlets, Mr. Reichert and his minions set out to destroy an entire fishery and the lives of the thousands of hard working Americans who depended on it.

This could have dealt a devastating blow to the U.S. longline fleet. Exacerbating a bad situation, it would have also resulted in the transfer of the uncaught quota from the strictly regulated U.S. boats to other vessels whose regulation was much less rigorous. Without question removal of the U.S. longline fleet would have had a negative impact on swordfish conservation.

Fortunately a swordfish management program to reduce fishing effort to where it was in balance with the resource had been put in place by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) years before Mr. Reichert and Pew “discovered” swordfish. By the time the Pew people and the Pew dollars entered the fray this program was already paying obvious conservation dividends. Then a closure of swordfish nursery areas off Florida, a closure which was supported by the U.S. longline fleet, was also put in place. This assured the recovery of the swordfish stock in the Western North Atlantic.

This was a testament to fisheries management based on sound science, not on media hype only affordable by multi-billion dollar corporations and foundations. In spite of self-serving claims to the contrary, the Pew peoples’ prodigious yet misguided efforts to scuttle the pelagic longline fleet – and their obvious lack of understanding of swordfish management – changed virtually nothing about the fishery or about how it was being managed.

But what has changed in the intervening years is the way in which the rest of the (non-Pew) world looks at pelagic longlining in general and the U.S. pelagic longline fleet in particular. Thanks to significant efforts by the U.S. participants in this fishery, they have become the undisputed world leaders in developing and implementing fishing gear and fishing techniques to drastically reduce or eliminate the incidence of bycatch in their fishery. And despite Mr. Reichert’s dire predictions and those of Pew’s stable of scientists, the doom and gloom predicted for swordfish if longlining was allowed to continue never developed. Today, as the pelagic longline fishery continues, the swordfish stock is fully rebuilt. In fact, the fishery is in such good shape that it was recently certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council.

So now Bluefin tuna

To quote the inimitable Yogi Berra, “it’s déjà vu all over again.” Fifteen years later the same cast of characters and the same organizations are using the same tired and ineffective strategy funded by the same sources to derail the management of another highly migratory fish species, the Atlantic bluefin tuna (ABT).

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), the same body that is responsible for swordfish management in the Atlantic, is holding a meeting of fisheries scientists and managers in Montreal at the end of this month to review the ABT stock assessment. The outcome of this review will have much to do with determining what the total allowable catch (TAC) of these valuable fish will be in the coming years. The TAC is divided between rereational fishermen, rod and reel commercial fishermen, harpooners, purse seiners (currently none are in the U.S. fishery) and pelagic longliners (who don’t target ABT but do take some incidentally).

While the public’s view of the value of these fish has been purposely distorted – each year one fish, supposedly the first and the best of the year, is sold at a Japanese auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars as a marketing ploy – they are valuable, with a prime fish bringing thousands of dollars (the National Geographic Channel offers a largely accurate portrayal of the rod and reel ABT fishery in its series Wicked Tuna).

In what is no surprise to anyone with even a nodding acquaintance with fisheries management issues, the folks at Pew have mounted yet another well-funded campaign to influence the outcome of this ICCAT assessment review. They are using the same flashy and expensive techniques and have enlisted a similar claque of experts to “save the tuna” as they used in the late 90’s to save the swordfish.

As was so convincingly demonstrated by the complete recovery of the swordfish stocks in spite of continued harvesting by the longline fleet, Pew science as voiced by Pew scientists was then far from the last word in the world of fisheries management. That hasn’t changed. Nor has their strategy. The same hackneyed messages of doom and gloom by the same overwrought scientists are presented as if they represent the main stream of fisheries research.

Rather than being swayed by their efforts to make the playing field at the upcoming meeting in Montreal as uneven as the billions of dollars backing them up will allow, it’s crucial that the independent science as espoused by the independent scientists speak for itself.

As with swordfish almost a generation ago, we trust that the scientists and managers in Montreal this week will not be swayed by all of the hyperbole that they will find aimed directly at them, will evaluate the existing science for what it is, not for what the Pew people will try to tell them it is, and make decisions that are right for the fish and right for the fishermen.

We should note here that there seems to be no limit to what the people at the Pew Trusts will spend in their attempts to convince anyone who will listen to reduce or eliminate fishing but when it comes to investing even negligible resources into efforts to more accurately and extensively sample the fish stocks they seem so intent on saving, something that everyone agrees is necessary for more effective management, they seem singularly uninterested.

NILS STOLPE: The New England groundfish debacle (Part IV): Is cutting back harvest really the answer?

The “blame it all on fishing” management philosophy “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” (A. Maslow, 1966, The Psychology of Science)

The “blame it all on fishing” management philosophy “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” (A. Maslow, 1966, The Psychology of Science)

NILS STOLPE Fishnet USA – While it’s a fact that’s hardly ever acknowledged, the assumption in fisheries management is that if the population of a stock of fish isn’t at some arbitrary level, it’s because of too much fishing. Hence the term “overfished.” Hence the mandated knee jerk reaction of the fisheries managers to not enough fish; cut back on fishing. What of other factors? They don’t count. It’s all about fishing, because fishing is all that the managers can control; it’s their Maslow’s Hammer. When it comes to the oceans it seems as if it’s about all that the industry connected mega-foundations that support the anti-fishing ENGOs with hundreds of millions of dollars a year in “donations” are interested in controlling. Read the article here

Federal fisheries enforcement and the 2012 election – a purposeful cover-up? By Nils Stolpe

Here are the facts.

Federal fisheries enforcement and the 2012 election – a purposeful cover-up?

Fact: Senator Scott Brown (Republican) and candidate Elizabeth Warren (Democrat) are in a close race for one of the two Massachusetts seats in the United States Senate.

Fact: A majority in the United States Senate, which is now in the hands of the Democratic Party, is considered by many pundits to be “up for grabs” in the rapidly approaching election, and the outcome in Massachusetts will be critical in determining which party controls the Senate – and the United States Congress – starting in 2013.

Fact: Senator Scott Brown has been an ardent supporter of the commercial fishing industry and has been particularly outspoken about an ongoing investigation of corruption at the highest levels of the enforcement branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Fact: New Englanders in general and residents of Massachusetts in particular tend to be extremely supportive of their fishing communities and of the fishing heritage that has played such a significant role in shaping the character of their coastline.

Fact: A 514 page report on the follow-up investigation by Special Master Charles Swartwood of NOAA enforcement abuses of fishermen and fishing associated businesses centered in New England and primarily in Massachusetts was completed and delivered to the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce in March of 2012.

Fact: In spite of strong bipartisan Congressional prodding to make the report public, prodding in which Senator Scott Brown has assumed a leadership role, (Acting) Secretary of Commerce Rebecca Blank has refused to do so. To her credit Elizabeth Warren, his opponent, has been seeking the release of the report as well.

Fact: Massachusetts Senator John Kerry’s brother, Cameron Kerry, is general counsel of the Department of Commerce. READ MORE

Glass fibers – the rest of the story????? by Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet-USA

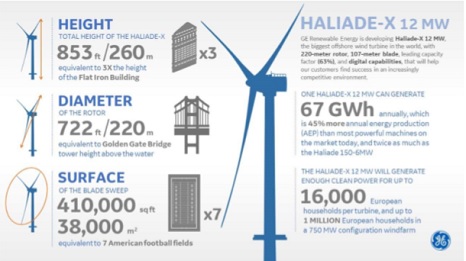

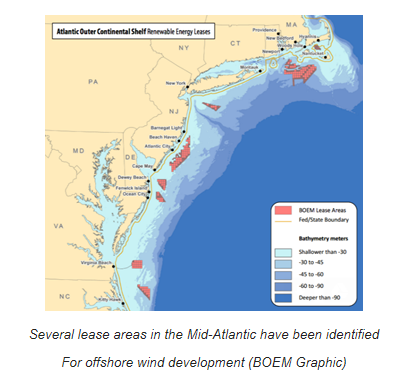

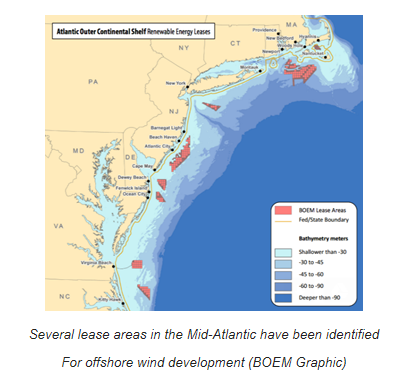

Floating around (sorry!) is the surprising story that the fiberglass that is being donated gratis to our oceans by the offshore wind industry is harmless because the fibers that make it up are chemically inert. Reassuring, isn’t it? Well, in words made immortal by George and Irwin Gershwin in Porgy and Bess, “it ain’t necessarily so.” To put those immortal words in the proper real world (not NOAA or BOEM scientist’s) perspective, the asbestos fibers that are still being used legally in a whole bunch of manufacturing processes today are chemically inert on their own. You can chomp on and swallow asbestos fibers to your heart’s content, as long as they stay in large chunks, with no ill effects. According to the National Library of Medicine “asbestos fibers are basically chemically inert, or nearly so. They do not evaporate, dissolve, burn, or undergo significant reactions with most chemicals.” So what happens when a huge fiberglass rotor on an offshore generator (300+ feet long and still enlarging as wind generators become larger-and more efficient) delaminates and takes a dive into one of our oceans? more, >>CLICK TO READ<< 15:52

Floating around (sorry!) is the surprising story that the fiberglass that is being donated gratis to our oceans by the offshore wind industry is harmless because the fibers that make it up are chemically inert. Reassuring, isn’t it? Well, in words made immortal by George and Irwin Gershwin in Porgy and Bess, “it ain’t necessarily so.” To put those immortal words in the proper real world (not NOAA or BOEM scientist’s) perspective, the asbestos fibers that are still being used legally in a whole bunch of manufacturing processes today are chemically inert on their own. You can chomp on and swallow asbestos fibers to your heart’s content, as long as they stay in large chunks, with no ill effects. According to the National Library of Medicine “asbestos fibers are basically chemically inert, or nearly so. They do not evaporate, dissolve, burn, or undergo significant reactions with most chemicals.” So what happens when a huge fiberglass rotor on an offshore generator (300+ feet long and still enlarging as wind generators become larger-and more efficient) delaminates and takes a dive into one of our oceans? more, >>CLICK TO READ<< 15:52

Glass fibers – the rest of the story????? by Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet-USA

September 12, 2024

Floating around (sorry!) is the surprising story that the fiberglass that is being donated gratis to our oceans by the offshore wind industry is harmless because the fibers that make it up are chemically inert. Reassuring, isn’t it?

Floating around (sorry!) is the surprising story that the fiberglass that is being donated gratis to our oceans by the offshore wind industry is harmless because the fibers that make it up are chemically inert. Reassuring, isn’t it?

Well, in words made immortal by George and Irwin Gershwin in Porgy and Bess, “it ain’t necessarily so.”

To put those immortal words in the proper real world (not NOAA or BOEM scientist’s) perspective, the asbestos fibers that are still being used legally in a whole bunch of manufacturing processes today are chemically inert on their own. You can chomp on and swallow asbestos fibers to your heart’s content, as long as they stay in large chunks, with no ill effects. According to the National Library of Medicine “asbestos fibers are basically chemically inert, or nearly so. They do not evaporate, dissolve, burn, or undergo significant reactions with most chemicals.”

So what’s the problem with asbestos? Why is keeping us living, breathing, etc. critters as far as possible from any exposure to asbestos dust, asbestos powder, asbestos shavings, asbestos scrapings, asbestos dreams, etc. so important? Most simply, because finely divided asbestos dust, powder, etc., when it is ingested or inhaled (or added to a poultice or an ointment when the moon is full, for all I know) is definitely not good for any of us, contributing to quite a few rather unpleasant maladies/conditions that we’d all be better off without.

Obviously, knowing what we know now a material being “inert” is no guarantee that it is completely harmless to inhale or to ingest. Believing otherwise is to hearken back to the long-gone days of alchemy. Back then when a substance was considered bad, it was considered bad in any way, shape or form. While today asbestos, when in big enough chunks is probably ok (just don’t chew it for too long), in little, eensy, weensy amounts it’s a killer. Those microscopic bits and pieces of asbestos can raise hell with some living tissues that they come into contact with. And they often do.

That’s the problem with asbestos.

So what’s the potential problem with glass fibers embedded in a plastic matrix that we call fiberglass (or fiber reinforced plastic–FRP)? You know, the stuff that an almost 1,000 foot tall “windmill” just inadvertently “enriched” a whole bunch of our ocean waters surrounding Nantucket Island with.

I’ve written before about what effective grinding machines our oceans are. They are particularly so in areas of high oceanic energy. While the ocean depths are fairly calm and stable, with not a lot of turbulence or currents, the margins of the ocean basins are an entirely different proposition. Big rocks are turned into smaller rocks which are turned into sand which is turned into silt. All because of the friction of being rubbed together with other rocks, with shell fragments, by the natural processes that go on in the shallow waters that characterize the ocean margins.

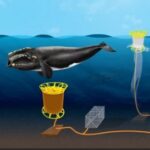

So what happens when a huge fiberglass rotor on an offshore generator (300+ feet long and still enlarging as wind generators become larger-and more efficient) delaminates and takes a dive into one of our oceans? In fairly short (geologically speaking) order it’s broken into thousands of smaller glass fibers embedded in a possibly “defective” plastic matrix held together with possibly “defective” adhesives. It gets ground up. And it’s very likely that a significant amount of it gets ground up into silicon “shards”-some of which become incorporated into the plankton.

That’s very possibly one of the initial steps in turning giant wind turbine blades into what will eventually become microscopic glass microfilaments.

Many of the filter-feeders out there, either living in or attached to the bottom, or floating around as part of the plankton, have been gifted by evolution with the ability to (sometimes) pick and choose amongst planktonic food and a bunch of non-food that has been cluttering up the oceans for eons. The food gets eaten. The non-digestibles either get dumped or get incorporated into the oceanic food chain.

We don’t have much of a clue about the effects on living creatures- including Homo sapiens-of these silicon shards once the ocean currents have been grinding them up with an endless procession of waves. (According to Wikipedia, “silicosis is a form of occupational lung disease caused by inhalation of crystalline silica dust. It is marked by inflammation and scarring in the form of nodular lesions in the upper lobes of the lungs. It is a type of pneumoconiosis. Silicosis, particularly the acute form, is characterized by shortness of breath, cough, fever, and cyanosis.” There is no known cure.)

Likewise, we don’t have a clue about whether those oceanic filter feeders are evolved enough (pls forgive me, C. Darwin!) to be able to discriminate between harmless and “dangerous” microfibers, whether glass or asbestos, without incorporating them into their own tissues (and subsequently into ours). And it appears as if Scandinavia’s most gifted engineers and most canny investors aren’t concerned in the slightest. (We also shouldn’t forget our own home court “heroes” in NOAA and BOEM.)

Suppose that those filter feeding mollusks (clams and oysters) that various organizations are so assiduously trying to reestablish in New York harbor or various other estuaries that were once home to extensive shellfish beds, are finally re-established? Being filter feeders, they are going to pump in bad (contaminated) water, extract sustenance from it as they tirelessly pump it in and out, and then dump the indigestibles pseudo feces (as they’re called in the technical literature) “over the side.” Do you think there’s a chance that among those indigestible pseudofeces there might be some silicon shards? Do you think anyone knows? Do you think anyone cares? President Biden and Governor Murphy and a few other kindred souls-as well as a bunch of Scandinavian technical types and investors-don’t seem to be all that interested, but maybe they should be.

How long would it take a bunch of glass microfilaments that started out as part of a 300+ foot long propeller spinning around in a wind driven generator off Nantucket to end up as “crystalline silica dust?” How much of that dust might render those clams or oysters that have incorporated it into their tissues toxic–either to fish lovers or to other edible critters swimming or crawling around out there-that we might have occasion to eat? And how many independent researchers are concerned?

Perhaps our near-shore worries should be directed towards just a bit more than stumbling by luck over some errant bits of flotsam and jetsam which have been released into our coastal waters or washed up on our beaches.

Blame it all on what we’re catching! By Nils E. Stolpe

FishNet-USA/04/01/06 – The entire focus of what is considered fisheries management today is on first blaming (generally commercial) fishing for any situation involving the perception that there are not enough fish, and then controlling (generally commercial) fishing to return a population of fish to what is presumed to be some optimum level. And most recently this has even been extended to restoring once healthy habitat that has been supposedly compromised by (generally commercial) fishing.